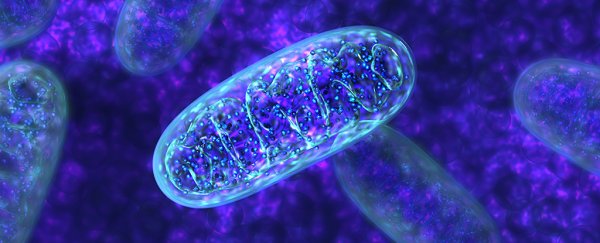

According to established scientific knowledge, complex cells (called eukaryotic cells) can't survive without mitochondria - tiny organelles that control respiration and power movement and growth. You can think of them as tiny batteries converting energy so that cells can go about their business, but they perform other key jobs, too. They are, as the common adage goes, the powerhouse of the cell.

Now, scientists working in Canada and the Czech Republic have made a surprising discovery: a eukaryotic cell without these mitochondrial batteries. It's an unprecedented find that's likely to change our thinking about how some types of cells can exist and grow. In other words, life is more flexible than we thought.

"[Mitochondria] were considered to be absolutely indispensable components of the eukaryotic cell and the hallmark of the eukaryotic cell," team leader, Anna Karnkowska from the University of British Columbia told Nell Greenfieldboyce at NPR.

The microbe in question originally came from a pet chinchilla, and after sequencing the gut microbe's genome, there was a complete lack of evidence that it made mitochondrial proteins. That was "a great surprise", says Karnkowska. "That should theoretically kill the cell - it shouldn't exist," she added.

Karnkowska and her colleagues think the cell uses a different technique for assembling iron-sulphur clusters - one of the main roles of mitochondria, which helps build certain proteins. The hypothesis is that the microbe borrows some bacterial genes to perform the same function.

As this organism's ancestors did contain small mitochondria, Karnkowska and her colleagues think the organelles have been lost fairly recently, in terms of evolutionary history. Now, the researchers are hopeful of finding other mitochondria-free eukaryotes.

"This is a discovery of fundamental importance: we now know that eukaryotes can live happily without any remnant of the mitochondria," evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin from the US National Centre for Biotechnology Information, who wasn't involved in the study, told Science's Mitch Leslie.

A similar claim was made about the human gut parasite Giardia: scientists believed it is free of mitochondria, but studies eventually discovered the presence of mitochondria 'relics' or remnants. The new findings are on a different level - it appears that this newly analysed organism, called Monocercomonoides, really can work without mitochondria.

It's perhaps down to the lack of oxygen in the guts of chinchillas that Monocercomonoides have evolved to work without the usual energy converter, the researchers suggest, although a detailed microscopic analysis is likely required in order to confirm the findings.

"[Monocercomonoides] lives in an area without oxygen and, therefore, can get rid of a lot of biochemistry that you and I would need in our cells to survive," evolutionary biochemistry researcher Mark Van Der Giezen from the University of Exeter in the UK, who wasn't involved in the research, told NPR.

"This organism managed to adapt in such a way that it could lose an organelle, which every textbook will tell you is an essential feature of eukaryotes. That's pretty amazing. It shows you that life is extremely creative in finding a way to eke out an existence."

The findings have been published in Current Biology.