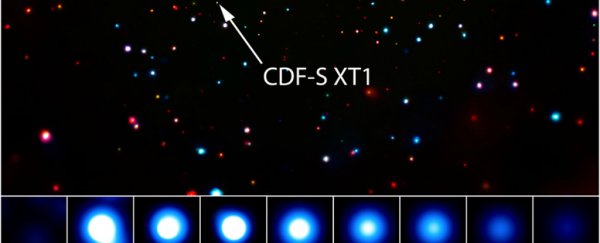

Scientists have taken the deepest X-ray image of our Universe to date - and within it, they've found evidence of a huge, unexplained explosion coming from a galaxy around 10.7 billion light-years away.

The galaxy itself appears to be fairly faint and unremarkable, but in October 2014, it suddenly became at least 1,000 times brighter over a few hours, before fading into oblivion again. No astronomical phenomenon that scientists currently know of can explain the behaviour.

"We may have observed a completely new type of cataclysmic event," said one of the researchers Kevin Schawinski, from ETH Zurich in Switzerland.

"Whatever it is, a lot more observations are needed to work out what we're seeing."

The mysterious explosion was so powerful that, for a few minutes, the X-ray source produced 1,000 times more energy than all the stars in that galaxy.

No event similar has ever been detected anywhere else in the Universe.

Chandra/NASA

Chandra/NASA

"Ever since discovering this source, we've been struggling to understand its origin," said team member Franz Bauer, from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

"It's like we have a jigsaw puzzle but we don't have all of the pieces."

While it might sound like researchers are stumped, there are a few potential hypotheses going around that could explain the strange explosion. Out of the three main ones, two of them centre around gamma-ray bursts (GRBs).

For those who aren't familiar, GRBs are the brightest electromagnetic events known to occur in our Universe.

These bursts are extremely high-energy explosions that occur in distant galaxies, and are thought to be released when a massive star collapses in on itself, or by the merging of two neutron stars, or a neutron star and a black hole.

If these GRBs happen to be pointing towards Earth when they erupt, we can detect the jet of gamma-rays bombarding us, before it tapers and we're flooded with weaker radiation, such as X-rays.

One possible idea is that this unexplained X-ray explosion could be us picking up a GRB that's not pointed at Earth - something we haven't done before, so it would look new to us. Or it could be evidence of a GRB that lies beyond the small galaxy.

A third possibility is that a black hole shredded a white dwarf star in the distant galaxy.

Getting a better idea of how these events occur could help shed some light on this latest explosion.

"None of these ideas fits the data perfectly," said researcher Ezequiel Treister, also from Chile's Pontifical Catholic University.

"But then again, we've rarely if ever seen any of the proposed possibilities in actual data, so we don't understand them well at all."

The strange X-ray blast was picked up by NASA's space-faring Chandra X-ray Observatory, which monitored the distant galaxy for a total of 2.5 months over the past 17 years, and detected no evidence of a similar event before or since.

With the help of data from the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes, the researchers were able to narrow down the source of the X-ray burst to a small galaxy about 10.7 billion light-years from Earth, located in a region of the night sky known as the Chandra Deep Field South.

The researchers are now planning to trawl back through the Chandra archive, as well as use data from the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton telescope and NASA's Swift satellite, to find any other evidence of a similar event occurring in the Universe that might have been missed because of how short-lived the explosion was.

They'll also be following up with more Chandra observations on the galaxy.

These are far from the only unexplained signals we've picked up in the distant Universe - fast radio bursts are another mysterious source of huge amounts of energy, although researchers are slowly beginning to narrow down the potential source of these events.

While it's tempting to write these kinds of events off as aliens, the reality is that there's a whole lot going on in our Universe that we don't yet understand or know about.

And studying strange bursts of energy like this one is the first step to understanding what we face when venture away from the safety of our planet in the decades to come.

The research will be published in the June issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and you can read it for free now at arXiv.org.