Conventional supercomputers can perform amazing, almost unimaginably complex calculations – but they're expensive, a huge power drain, they run incredibly hot, and tend to be about as big as your house (sometimes even bigger).

But what if there were a radically different approach to computing that didn't rely on the technology of today's digital circuits? That's the thinking behind an amazing new biological supercomputer model developed by an international team of researchers, which uses proteins in place of electrons to relay information around a living microchip.

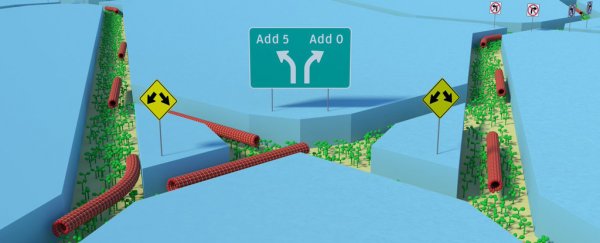

The chip they've created is tiny – measuring about 1.5 cm squared – but if you were to zoom in on it you'd find it to be a teeming, city-style grid. Protein strings travel along the streets of this minute metropolis, which are in fact extremely slight channels etched into the circuit.

"We've managed to create a very complex network in a very small area," said bioengineer Dan Nicolau Sr. from McGill University in Canada, who has collaborated on the biocomputer concept with researchers from Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands for the better part of a decade. "This started as a back of an envelope idea, after too much rum I think, with drawings of what looked like small worms exploring mazes."

In a sense, the biological agents – protein filaments, in the prototype developed – replace the function of electrons in a conventional microchip. The proteins are powered by the chemical adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which facilitates the transfer of energy at the cell level in all living organisms.

While the living computer model is far from being ready for prime time, the researchers say its small size, extreme energy efficiency, and minimal heat output could lead to the development of a new generation of small, sustainable supercomputers capable of parallel computing – performing a potentially vast number of calculations simultaneously, the hallmark of traditional supercomputers.

As described in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the scientists tested their proof-of-concept biocomputer with a mathematical problem, with the biological agents inside the chip processing the calculation by their directed movement within the circuit.

It's early days, but now that we know the idea works, living computers could well form an important part of the supercomputers of tomorrow – perhaps even fusing with (and augmenting) traditional silicon machines.

"Now that this model exists as a way of successfully dealing with a single problem, there are going to be many others who will follow up and try to push it further, using different biological agents, for example," Nicolau Sr. said.

"It's hard to say how soon it will be before we see a full scale bio super-computer. One option for dealing with larger and more complex problems may be to combine our device with a conventional computer to form a hybrid device. Right now we're working on a variety of ways to push the research further."