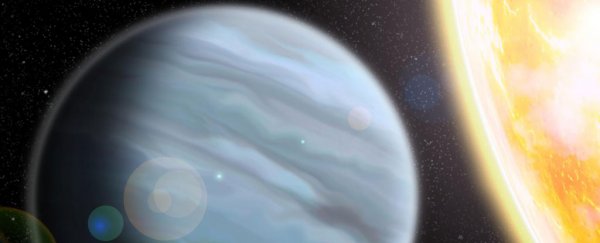

Astronomers have found a giant exoplanet larger than Jupiter, but with extremely low mass - a composition that gives this mysterious 'puffy planet' a density very similar to styrofoam.

The team who found KELT-11b, which orbits a star located about 320 light-years from Earth, says this "extraordinarily inflated" world is the third-lowest density planet with a precisely measured mass and radius that has been discovered – and this oddball, lightweight sphere could tell us more about how such strange exoplanets evolve.

"It is highly inflated, so that while it's only a fifth as massive as Jupiter, it is nearly 40 percent larger, making it about as dense as styrofoam, with an extraordinarily large atmosphere," says astronomer Joshua Pepper from Lehigh University in Pennsylvania.

Apart from KELT-11b's unusual density, one of the things that makes the exoplanet stand out is its host star's extreme brightness. The star, called KELT-11, is in the process of evolving into a red giant, meaning it's started using up its nuclear fuel, fusing hydrogen in a shell outside its core.

Scientists now predict that sometime within the next 100 million years, KELT-11b will end up being engulfed by its host star, as KELT-11's outer layers expand to consume the styrofoam-like world.

Walter Robinson/Lehigh University

Walter Robinson/Lehigh University

That engulfment won't take long, either, since the planet hangs very close to its host, orbiting KELT-11 in less than five days.

But before that engulfment happens, the puffy planet stands to teach scientists more about its atmospheric makeup, thanks to the intense brightness generated by KELT-11.

The star is in fact the brightest visible star in the Southern Hemisphere that's known to host a transiting planet – referring to how KELT-11b passes in between the star and Earth during its orbit.

That transit is how astronomers often detect exoplanets, as the amount of light space telescopes receive from these distant stars dips slightly as the exoplanet passes in front of them.

But in the case of KELT-11, the sub-giant's intense luminosity meant that the dip in light caused by KELT-11b's transit was barely recognisable to astronomers using the KELT (Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope) survey – a pair of robotic telescopes located in Arizona and South Africa.

"This discovery was very challenging. The original KELT observations of the star – its light curve – showed only a hint of the transit," Pepper told Tomasz Nowakowski at Phys.org last year, when the team first announced their findings prior to peer-review.

"Because the transit is both shallow (a little under 0.3 percent change in brightness) and long, it was very difficult to obtain reliable, complete confirmation observations."

Follow-up observations eventually confirmed the existence of KELT-11b, and now the same extreme backlight that made its initial discovery so difficult could help the team figure out the composition of its atmosphere. And that could provide clues on how this styrofoam world got so unusually inflated.

As it stands, KELT-11b is about twice as large as the scientists can explain, given its mass and proximity to its host, but now that we know it's there, it's a great opportunity to find out more about these styrofoam-like planets, and what makes them so big but so sparse at the same time.

"We think that KELT-11b will be a great test case to help us understand the mechanism that causes inflated planets," Pepper told Phys.org.

"Furthermore, since the host star has evolved onto the sub-giant branch and is reaching the end of its life, we hope that we can study the behaviour of planetary systems at the end-stage of their star's lifetime."

The findings are reported in The Astronomical Journal.