In a world-first experiment, scientists have managed to grow a functional, artificial embryo from scratch, using two types of stem cells to build life in a Petri dish.

The stem cells were grown outside the body in a blob of gel, and were able to transform into several early-stage internal organs - just like in a regular embryo. Researchers are now hoping the technique will solve some major mysteries about the beginnings of life.

"It has anatomically correct regions that develop in the right place and at the right time," lead researcher, Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz from the University of Cambridge in the UK told The Guardian.

"This was the most amazing thing for us."

Previous attempts to grow an artificial embryo have fallen short, because they've only involved embryonic stem cells (ESCs) - stem cells that form the free-floating ball of cells called a blastocyst once the egg has been fertilised.

The problem was that life doesn't simply grow from embryonic stem cells - two other types of stem cells, called extra-embryonic trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) and primitive endoderm stem cells - are also vital for proper development.

Coordinating with the ESCs, these additional stem cells form the placenta and yolk sac, which ensure that the organs can develop properly, and are given a steady supply of nutrients.

So Zernicka-Goetz and her team tried using a combination of genetically-modified mouse ESCs and TSCs, and built a 3D, gel-based scaffold that the stem cells could grow around to mimic the form of a natural embryo.

"We knew that interactions between the different types of stem cell are important for development, but the striking thing that our new work illustrates is that this is a real partnership - these cells truly guide each other," she says in a press statement.

"Without this partnership, the correct development of shape and form and the timely activity of key biological mechanisms doesn't take place properly."

After around 4.5 days, the researchers had several living embryos that looked just like regular mouse embryos - even down to the way they started differentiating into various tissues and organs.

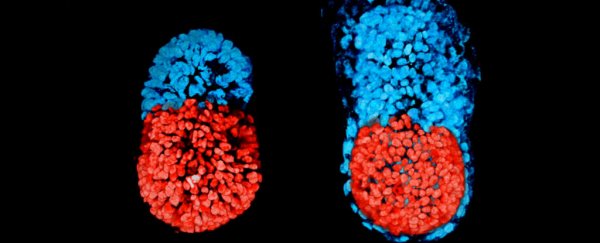

At the 7-day mark, the embryo had arranged itself into two main parts - the beginnings of a placenta, and the actual mouse itself.

In the image below, you can see the mouse embryo at 96 hours (left), and at 48 hours from the blastocyst stage (right).

The red part is embryonic, and the blue extra-embryonic, which means it would eventually form the placenta:

University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

At no stage in the process was an egg or a sperm cell ever required to grow life.

"They are very similar to natural mouse embryos," Zernicka-Goetz told Andy Coghlan at New Scientist.

"We put the two types of stem cells together - which has never been done before - to allow them to speak to each other. We saw that the cells could self-organise themselves without our help."

The embryos reached a development stage roughly equivalent to a third of the way into a mouse pregnancy before they were terminated.

The researchers admit that the embryo would have struggled to develop beyond this point without the addition of primitive endoderm stem cells to grow the yolk sac - a thick membrane that attaches to the embryo and supplies its nutrients and blood cells until the placenta becomes fully functional later on.

And as cool as growing life from scratch is - the mind truly boggles at the possibilities - the goal of the research wasn't to advance artificial life, but to give us a window into what actually happens at the early stages of it.

During the first trimester of human pregnancy, more than two out of three will result in a miscarriage, and no one's quite sure why.

By growing artificial life that requires no egg or sperm cells, and can be grown outside the womb, researchers would have a steady supply of 'test' embryos that they can tease the tiny details of early life from.

The next step will be to see if the technique can work using human stem cells - something the team is confident that they can achieve.

"We think that it will be possible to mimic a lot of the developmental events occurring before 14 days using human embryonic and extra-embryonic stem cells using a similar approach to our technique using mouse stem cells," Zernicka-Goetz explained in a statement.

"We are very optimistic that this will allow us to study key events of this critical stage of human development without actually having to work on embryos. Knowing how development normally occurs will allow us to understand why it so often goes wrong."

The research has been published in Science.