In a world first, scientists have successfully bred mice without using fertilised eggs, and the results could have implications for endangered species with low female numbers, and one day even humans.

The experiment, performed by embryologists at the University of Bath in the UK, also suggests that egg cells might not be as vital to reproduction as we've assumed, with the team proposing that something as simple as a skin cell could act as an adequate replacement.

"This is [the] first time that full term development has been achieved by injecting sperm into embryos," said one of the team, Tony Perry.

"Our work challenges the dogma, held since early embryologists first observed mammalian eggs around 1827, and observed fertilisation 50 years later, that only an egg cell fertilised with a sperm cell can result in live mammalian birth."

The success of the experiment not only brings into question the assumption that only a fertilised egg can start dividing to give rise to life - it also suggests that something other than an egg cell can reprogram sperm to allow for embryonic development.

Until now, no one has been able to demonstrate that any other type of cell is capable of combining with sperm to produce offspring, and by proving that assumption wrong, the team has opened up the possibility for other kinds of cells being capable of doing the same thing.

"What we're talking about are different ways of making embryos," Perry told Ian Sample at The Guardian. "Imagine that you could take skin cells and make embryos from them? This would have all kinds of utility."

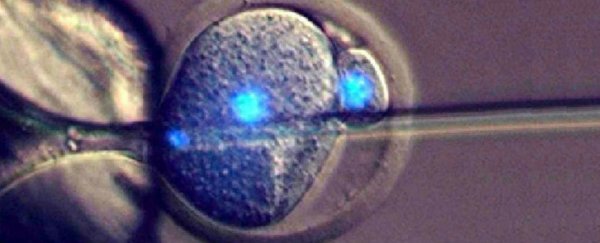

For the experiment, Perry and his team extracted unfertilised eggs from female mice, and figured out how to coax them into becoming 'pseudo-embryos' called parthenogenotes.

Previous research has shown how if you take unfertilised mouse eggs and pop them into a chemical bath containing a type of salt called strontium chloride (SrCl2), you can basically 'trick' them into dividing into daughter cells, as if they'd been fertilised by a sperm cell.

In certain species of reptiles, these parthenogenetic embryos can grow into perfectly healthy offspring - with absolutely no males required - but in mammals, they've never survived, usually dying off within a few days.

The researchers decided to see what would happen when they injected sperm cells into their newly divided daughter cells, and found that the parthenogenetic embryos survived beyond the usual few days.

So they implanted the embryos into female mice, and report that they produced 30 pups with a success rate of 24 percent.

So far, the pups all appear to be perfectly heathy. Some even went on to have pups of their own - via more 'traditional' methods - and some of those had pups too.

"As far as we can tell, the baby mice were normal and healthy," Perry told George Dvorsky at Gizmodo.

"We checked how long they lived, and their life expectancies were similar - in some cases longer - to those of controls. We found that the mice reproduced efficiently … and had similarly healthy offspring."

Some of the babies. Credit: University of Bath.

Some of the babies. Credit: University of Bath.

Now, If you're wondering what all the fuss is about, because they basically just used an egg and a sperm cell to create babies, the key here is that the daughter cells produced by the parthenogenetic embryos are completely different from daughter cells produced by a fertilised egg.

"Unlike normal egg cells, they can divide to form new cells, which Perry says makes them more like other cells in the body, like skin," Andy Coghlan explains for New Scientist.

The next step is for the team to run through the same process, but this time replace the unfertilised eggs with skin cells, to see if a similar result can actually be achieved.

"Will we be able to do that? I don't know," Perry told The Guardian. "But I think, if it is ever possible, one day in the distant future people will look back and say this is where it started."

Of course, it's tempting to think about the possibility of somehow making human babies out of sperm cells and skin cells, or applying the method to mammal species with very few individuals left, but at this stage, it's too soon to tell if the technique will work on something other than mice.

We'll just have to wait and see, but at least we now have a back-up plan if one day all the female mice decide to call it quits.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.