For the first time, researchers have observed the creation of ice crystals on individual atmospheric particles, giving an unprecedented glimpse at the way ice clouds form in our atmosphere.

The process, called ice nucleation, occurs when a particle attracts water vapour and forms ice crystals, which become the core of the wispy cirrus clouds that often hang in the sky above our heads. Observing this microscopic chain of events first-hand isn't easy, but it's vital for our understanding of how clouds take shape and both cool and heat the planet.

"This is one of the most critical but least understood parts of the process of how cold clouds form," said one of the team. Bingbing Wang, from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

"The fundamental process of how ice grows is relatively well understood, but ice nucleation – that moment when the first group of molecules comes together – remains a big challenge."

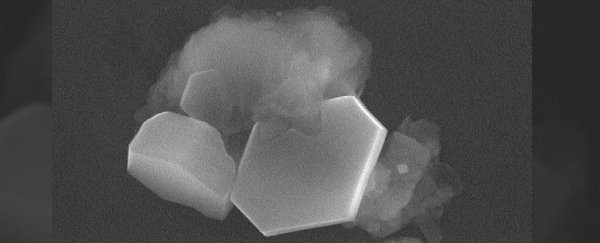

Ice crystals forming around the kaolinite particle in the very first seconds of the formation of an ice cloud. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Ice crystals forming around the kaolinite particle in the very first seconds of the formation of an ice cloud. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

To recreate the process in the lab, the team had to replicate conditions found high above Earth's surface – at an altitude of about 6 kilometres (20,000 feet), where cirrus clouds form in the sky.

At this height, relative humidity is high and temperatures are very low, meaning water vapour readily collects on any small particles floating in the atmosphere, before freezing in place as an ice deposit.

In the atmosphere, such airborne particles could be almost anything, including volcanic ash, aircraft emissions, or even microbes.

For their recreation of ice nucleation in the lab, the researchers used particles of a clay mineral called kaolinite. These particles are extremely small – just 2–3 microns in size, or less than one-tenth the width of a human hair.

The kaolinite was then placed in a highly confined climate-controlled chamber about the size of a poppy seed, which was photographed by an environmental scanning electron microscope.

This kind of microscope captures details at extremely high resolution, and was able to record ice crystals forming on the particle at just 50 nanometres wide, which is approximately one-thousandth the width of a human hair.

The poppy-seed-sized birthing chamber for the ice cloud crystals, being placed in an environmental scanning electron microscope. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

The poppy-seed-sized birthing chamber for the ice cloud crystals, being placed in an environmental scanning electron microscope. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

In the kaolinite experiment – and in another test using particles made from carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen – ice nucleation occurred at temperatures as low as 205 degrees Kelvin (minus 68 degrees Celsius, or minus 90 degrees Fahrenheit), with relative humidity from about 70 to 80 percent.

While scientists have studied ice nucleation before, the researchers say this is the first time the formation of ice crystals has been observed with such small starting particles, giving us a never-before-seen perspective on this truly minuscule phenomenon.

"We were able to monitor moment by moment the formation of an ice crystal, at nanoscale resolution and under atmospherically relevant conditions," said one of the team, atmospheric chemist Daniel Knopf from Stony Brook University.

"Doing so and knowing that this process is replicated a million times, resulting in a cloud visible to the naked eye, is tremendously exciting, and a huge step forward for our predictive understanding of cloud formation with important ramifications for climate."

You can discover more about the research in the video below:

The findings are published in Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics.