Scientists in the Netherlands have succeeded in writing data at the smallest scale ever, manipulating chlorine atoms one at a time to store a kilobyte of data in what's being called the world's 'smallest hard disk'.

Taking their inspiration from famous physicist Richard Feynman – who back in 1959 envisioned that one day individual atoms could be arranged to store information – the researchers actually coded a section of Feynman's speech on the topic into their atomic kilobyte.

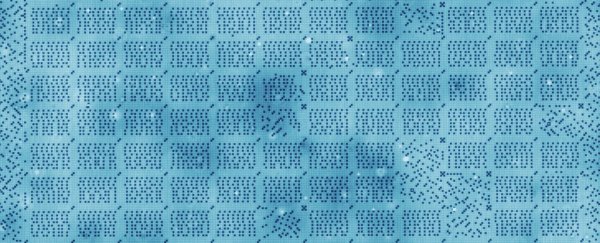

According to the team from the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at Delft University, writing data at this incredibly small scale – 1 kilobyte (8,000 bits) recorded in an area just 96 nanometres (nm) wide and 126 nm tall – enables a storage density of 500 terabits per square inch (Tbpsi), which is 500 times better than the capabilities of the best hard drives we use today.

"In theory, this storage density would allow all books ever created by humans to be written on a single post stamp," says lead researcher Sander Otte.

To create their record-setting data mechanism, the researchers used a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM), a tool that enables scientists to image and manipulate material at the atomic level. With the probe, they were able to physically arrange chlorine atoms on a copper plate, moving them one at a time to make up blocks of memory consisting of 64 bits, encoded in binary patterns that work much like miniature QR codes.

STM scan (96 nm wide, 126 nm tall) of the 1 KB memory, written to a section of Feynman's lecture, "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom". Credit: TU Delft/Ottelab

STM scan (96 nm wide, 126 nm tall) of the 1 KB memory, written to a section of Feynman's lecture, "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom". Credit: TU Delft/Ottelab

"You could compare it to a sliding puzzle," says Otte. "Every bit consists of two positions on a surface of copper atoms, and one chlorine atom that we can slide back and forth between these two positions. If the chlorine atom is in the top position, there is a hole beneath it – we call this a 1. If the hole is in the top position and the chlorine atom is therefore on the bottom, then the bit is a 0."

Because the technique enables data to be written at such an incredibly reduced scale compared to today's storage devices, it could hypothetically offer a massive boost in storage efficiency – shrinking the massive data centres that house our information in the cloud, and enabling consumer gadgets to become even more miniaturised.

But due to the coldness requirements for the memory to function, it may still be a while yet before your Spotify or Netflix streams to you courtesy of chlorine.

"In its current form the memory can operate only in very clean vacuum conditions and at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K, which is –196 degrees Celsius or –321 degrees Fahrenheit)," Otte explains, "so the actual storage of data on an atomic scale is still some way off. But through this achievement we have certainly come a big step closer."

You can find out more about the atomic memory and how the scientists developed it in the video below.

The findings are published in Nature Nanotechnology.