For the first time, scientists have reconstructed the route that HIV/ AIDS took to arrive in the US from the Caribbean in the early 1970s, and in doing so, have exonerated a man who has for years been accused of single-handedly introducing the disease to the States.

French-Canadian flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas was first referred to as Patient Zero in a 1984 study of homosexual men with AIDS, and since then, the charge has stuck. But DNA evidence has now revealed that HIV actually entered the US more than a decade earlier.

"No-one should be blamed for the spread of a virus that no-one even knew about," one of the researchers, Michael Worobey from the University of Arizona, told Nicola Davis at The Guardian.

"How the virus moved from the Caribbean to the US and New York City in the 1970s is an open question - it could have been a person of any nationality, it could have even been blood products."

The researchers say that not only was Dugas clearly not the first person in the US with HIV, accusations of him being Patient Zero likely stemmed from an unfortunate typo - one that the media at the time ran with, despite the original study indicating that he was unlikely to be the source.

As Davis reports, the original study referred to Dugas as "Patient O", which stood for "Outside of California", because he came from Quebec City in Canada. This went on to be misleadingly written as "Patient 0" - a term widely used to mean the first case of an outbreak.

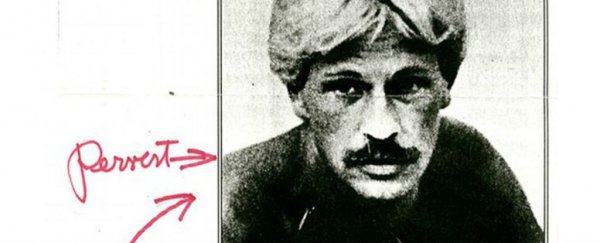

An annotated clipping of People Magazine in 1988. Credit: NIH

An annotated clipping of People Magazine in 1988. Credit: NIH

To figure out the truth, Worobey and a team of researchers from the US, the UK, and Belgium developed a new technique called RNA jackhammering to reconstruct the timeline of HIV-1 group M subgroup B - the most common strain of HIV in the West.

This technique allowed them to isolate several short fragments of RNA from old genetic samples, and stitch them together to build an entire genome of the HIV virus. This means they didn't have to rely on finding whole strands of fragile RNA in decades-old samples.

They gathered more than 2,000 serum samples collected from American men between 1978 and 1979, and from those, were able to construct eight almost intact RNA genome sequences of HIV-1 group M subgroup B.

All of these samples had been taken well before AIDS was officially recognised as a disease in the US in 1981 by the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Based on their new sequences, the team concluded that HIV spread from Africa to the Caribbean in 1967, from the Caribbean to New York in 1971, and then from New York to San Francisco in 1976.

They have not been able to identify how exactly the disease originally spread from the Caribbean to New York in the first place, but at least we've cleared Dugas's name once and for all.

And besides, blaming one person for the spread of a virus that has gone on to kill an estimated 35 million people around the world over the past four decades isn't really the point.

"In many ways the historical evidence has been pointing to the fallacy of this particular notion of Patient Zero for decades," one of the researchers, Richard McKay from the University of Cambridge, told The Guardian.

"This individual was simply one of thousands infected before HIV/AIDS was recognised."

The study has been published in Nature.