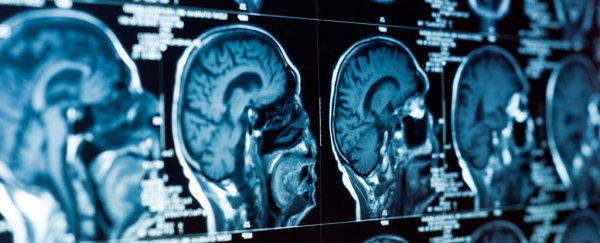

The region of the brain that serves as the physical source of feelings of depression has been identified, with new MRI data being the latest evidence to show that depression isn't just a 'frame of mind'.

Scientists have scanned the brains of more than 900 people, and the results suggest that feelings of loss and low self-esteem are tied to the functioning of the orbitofrontal cortex – a region of the brain associated with sensory integration, expectation, and decision-making.

"Our finding, with the combination of big data we collected around the world and our novel methods, enables us to locate the roots of depression, which should open up new avenues for better therapeutic treatments in the near future for this horrible disease," says computational psychiatrist Jianfeng Feng from the University of Warwick in the UK and Fudan University in China.

To isolate the brain mechanisms involved in depression, Feng's team recruited 909 people in China to take part in MRI brain scans. Of this group, 421 of the participants had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder (aka depression). The remaining 488 participants – who didn't have depression – acted as a control group.

The scans showed that depression is related to the neural activity of two different portions of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC): the medial OFC and lateral OFC.

The medial OFC becomes active when we receive rewards. In other words, when something good happens, the medial OFC fires up, and we feel good about it.

But the researchers found that the participants with depression showed weaker neural connections between the medial OFC and the brain's memory systems in the hippocampus.

It's not yet clear what the implications of this are, but it could mean that people with depression have a harder time accessing and recalling happy or positive memories.

In addition to displaying weaker connections with the medial OFC, depression patients in the study also showed stronger neural connections around the lateral OFC – which is involved with processing non-reward outcomes, such as punishments.

These stronger connections were made with parts of the brain including the precuneus – thought to be involved with our sense of self – and the angular gyrus, which is responsible for memory retrieval and attention.

All of which suggests that the heightened brain activity around the lateral OFC could mean that people with depression find it easier to relive negative experiences and harder to feel good about themselves.

Meanwhile, these effects seem to be compounded by the reduced medial OFC connectivity, which makes it harder for them to process happy memories. The worst of both worlds, so to speak.

When contrasting the neural activity of the depression patients who were taking medication for their condition with the neural activity of depression patients not on medication, the researchers found that the functional connectivity of the lateral OFC – processing non-reward outcomes like punishments – was lower in those who were medicated.

This suggests that existing antidepressants do have a positive effect in evening out these mechanisms in this part of the brain.

University of Warwick

University of Warwick

A better understanding of the underlying physical causes of depression could make a huge difference in how we fight the disease, because the current treatment method – trying one medication after another until something sticks – isn't effective, with roughly 50 percent of all first-time prescriptions failing to help those in need.

So on top of being further evidence that depression – and mental illness in general – is not just a frame of mind, the research could lead to new personalised medications that specifically target the orbitofrontal cortex and its two sub-regions for more effective relief.

The findings are reported in Brain.