For the first time, researchers have discovered supersonic plasma jets in Earth's upper atmosphere, and they're responsible for some pretty extreme conditions, including temperatures near 10,000°C (18,032°F).

These jets not only appear to be changing the chemical composition of Earth's ionosphere - they're actually pushing this atmospheric layer so far up, some of the planet's atmospheric materials are being leaked out into space.

More than a century ago, Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland proposed that vast electric currents powered by solar wind were travelling through Earth's ionosphere by the planet's magnetic field.

The ionosphere is an atmospheric layer spanning 75 to 1,000 km (46 to 621 miles) above Earth's surface, and once scientists finally figured out how to get satellites up there in the 1970s, the existence of these electric currents was confirmed.

Known as Birkeland currents, they carry up to 1 TW of electric power to the upper atmosphere - about a third of the total power consumption of the US in a year.

They're also responsible for the aurora borealis and aurora australis that light up the poles of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

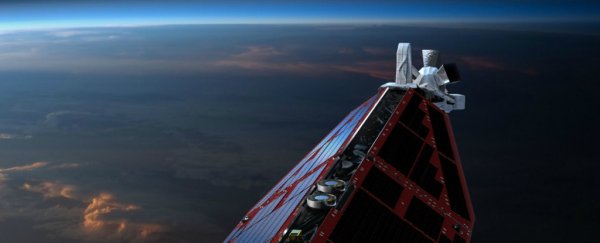

More recently, scientists from the European Space Agency (ESA) have sent a trio of Swarm satellites into the space between Earth's ionosphere and magnetosphere to investigate the Birkeland currents.

Initially, these satellites detected incredibly large electrical fields, which are generated in the ionosphere where upwards and downwards Birkeland currents are interacting above the planet like so:

ESA

ESA

Now the satellite trio has discovered what these electrical fields are driving - extreme supersonic plasma jets that have been dubbed 'Birkeland current boundary flows'.

"Using data from the Swarm satellites' electric field instruments, we discovered that these strong electric fields drive supersonic plasma jets," says one of the team, Bill Archer from the University of Calgary.

"They can drive the ionosphere to temperatures approaching 10,000°C and change its chemical composition. They also cause the ionosphere to flow upwards to higher altitudes, where additional energisation can lead to loss of atmospheric material to space."

Weirdly enough, thanks to some other recent observations from the Swam satellites, we now know that similar systems are at play both in Earth's upper atmosphere and deep inside its liquid outer core.

Back in December, the ESA team announced that their Swam satellites had detected an accelerating river of molten iron some 3,000 km (1,864 miles) below the surface of Earth, under Alaska and Siberia.

They found that this 420-km-wide (260-mile) jet stream had tripled in speed in less than two decades, and is currently headed towards Europe.

Like the supersonic plasma jets that are zooming through our upper atmosphere, this fast-moving jet of molten iron is directly related to Earth's magnetic fields.

Differences in temperature, pressure, and composition within the outer core create movements and whirlpools in the liquid metal, and together with Earth's spin, they generate electric currents, which in turn produce magnetic fields.

Having now discovered Earth's outer core and upper atmosphere jets, researchers will be better equipped to predict what our magnetic field is going to do next, and that's important, because it looks like the North Pole is actually in the process of shifting as we speak.

As we explained last year, since Earth's magnetic field seems to have been weakening at a rate of about 5 percent per century, the magnetic field is expected to flip, at which point the magnetic north and south poles will trade places.

"Further surprises are likely," ESA's Swarm mission manager, Rune Floberghagen, said at the time. "The magnetic field is forever changing, and this could even make the jet stream switch direction."

The most recent Swarm findings have been presented at the 4th Swarm Science Meeting and Geodetic Mission Workshop in Canada this week, and a peer-reviewed study on the results is expected in the coming months.