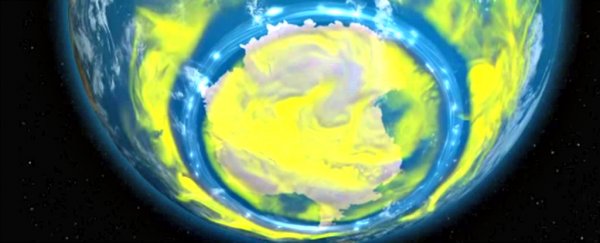

Scientists have found evidence that the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica is finally beginning to heal. If progress continues, it should be closed permanently by 2050.

The news comes almost 30 years since the world worked together to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals, so we're allowed to give ourselves a little pat on the back. "We can now be confident that the things we've done have put the planet on a path to heal," said lead researcher Susan Solomon from MIT.

In the '80s and '90s, the hole in the ozone layer was the environmental threat that everyone was worried about. After decades of pumping chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) into the atmosphere - through dry cleaning, aerosols, and old refrigerators - scientists found that the ozone over Antarctica had become seriously thin.

That's not great, seeing as the ozone layer is the shield that absorbs much of the Sun's harmful UV rays before they reach Earth.

To combat the problem, most countries on the planet signed the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which was a global treaty that governed the gradual phase-out of CFCs and other ozone-damaging chemicals.

And now researchers using new longitudinal measurements have shown that the hole is finally starting to heal, and has shrunk by 4 million square kilometres since its peak in 2000. That's roughly half the size of the mainland US.

It did expand to a record size in 2015 due to the eruption of the Chilean volcano, Calbuco, but if environmental progress continues, the hole should be fully closed by mid-century.

"Which is pretty good for us, isn't it?" said Solomon. "Aren't we amazing humans, that we did something that created a situation that we decided collectively, as a world, 'Let's get rid of these molecules'? We got rid of them, and now we're seeing the planet respond."

Since scientists first started noticing that the ozone hole was getting bigger in the mid-1980s, they've been monitoring ozone levels every year in October, when Antarctica moves out of its long winter months and gets sunnier - because chlorine only eats away at ozone when light and cold winds are present.

But the ozone hole starts opening up in August, and Solomon and her team thought they might get more accurate measurements if they tested levels in September, when the temperatures are still cold.

The team was able to show that as chlorine levels in the atmosphere decreased, the rate at which the ozone hole opens up has slowed.

"I think people, myself included, had been too focused on October, because that's when the ozone hole is enormous, in its full glory," said Solomon. "But October is also subject to the slings and arrows of other things that vary, like slight changes in meteorology. September is a better time to look because chlorine chemistry is firmly in control of the rate at which the hole forms at that time of year, that point hasn't really been made strongly in the past."

In addition to monitoring the September ozone levels from 2000 to 2015, the team measured the amount of sulphur dioxide emitted by volcanoes each year, which can add to ozone deterioration. They also compared their results with model simulations that predict ozone levels based on the amount of chlorine in the atmosphere each year.

They found that not only did their observations show that the hole was shrinking, it also matched the model's predictions, suggesting that more than half of the change had been driven by the decreasing chlorine in the atmosphere.

"It showed we can actually see a chemical fingerprint, which is sensitive to the levels of chlorine, finally emerging as a sign of recovery," said one of the researchers, Diane Ivy.

The research, which has been published in Science, also shows that we can actually fix some of the damage we've done to the environment when we work together.

"This is a reminder that when the world gets together, we really can solve environmental problems," Solomon told Gizmodo. "I think we should all congratulate ourselves on a job well done."