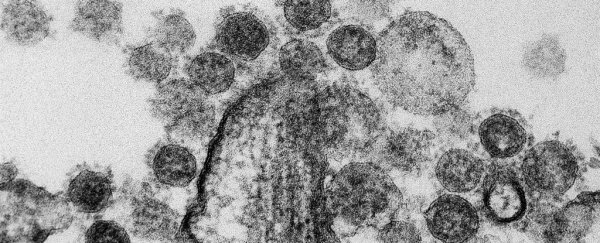

The US federal government has lifted an enforced moratorium on funding research into how to make viruses deadlier and more transmissible.

The moratorium, which was imposed three years ago, froze funding for what's called "gain of function" research: controversial experiments seeking to alter pathogens and make them even more dangerous. Now, the money is back on the table, giving those trials the green light once more.

The director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Francis S. Collins, announced the lifting of the moratorium on Tuesday, saying gain of function (GOF) research with viruses like influenza, MERS, and SARS could help us "identify, understand, and develop strategies and effective countermeasures against rapidly evolving pathogens that pose a threat to public health".

That may be true, but not everybody in the science community is welcoming the resumption of these contentious experiments.

According to some, the new flow of funding heightens the risk that unseen breeds of deadly engineered pathogens could escape lab containment – making their way to the public, or into the wrong people's hands.

"I am not persuaded that the work is of greater potential benefit than potential harm," molecular biologist Richard Ebright from Rutgers University told STAT.

To mitigate the risk, the NIH has unveiled a new framework to regulate funding approval for pathogen research, with panels to consider the scientific merits and potential benefits of proposed studies, "as well as the potential to create, transfer, or use an enhanced potential pandemic pathogen".

The new framework is intended to guide scientific panels in assessing proposed research into these 'enhanced' forms of potential pandemic pathogens (PPP), which are defined as viruses that are highly transmissible and likely capable of wide and uncontrollable spread in human populations, and also likely to cause significant morbidity and/or mortality in humans.

To secure funding through the new process, researchers will have to demonstrate that they have the capacity to conduct their pathogen research in safe and secure facilities, with backup plans to mitigate issues stemming from things like "laboratory accidents, lapses in protocol and procedures, and potential security breaches".

"We see this as a rigorous policy," Collins told The New York Times. "We want to be sure we're doing this right."

Many are not convinced.

The funding moratorium was initially enforced after a string of high-profile biocontainment blunders in the US, including the accidental exposure of workers at the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to anthrax, and a dangerous mishandling of avian flu samples, which saw a deadly strain unintentionally substituted for a benign sample.

Critics of the new framework say these kinds of accidents will be inevitable once again now that the ban is over, insisting that no matter how rigorously designed the new policy is supposed to be, the weakest link in all this – human error – remains unchanged.

According to those voices, all these enhanced, deadlier-than-ever pathogens aren't the most dangerous things in this cocktail: we are.

"A human is better at spreading viruses than an aerosol," epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health told STAT.

"The engineering is not what I'm worried about. Accident after accident has been the result of human mistakes."

Others are welcoming the renewed ability to make scientific progress in this controversial field, arguing that the benefits outweigh the risk – especially since natural viruses are always evolving by themselves anyway.

In other words, the threat of future pandemics can't ever be totally guarded against, whether or not we elect to study newly emerging viruses in a lab.

"There has been increased scrutiny of laboratories working in this area, which can lead to an even more robust culture of safety. But I also fear that the moratorium may have delayed vital research," chair of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, Samuel Stanley, told NPR.

"I believe nature is the ultimate bioterrorist and we need to do all we can to stay one step ahead."