Yellowstone has had a turbulent June. In just two weeks, the supervolcano that lies underneath the national park was hit with 878 earthquakes.

The dense series of earthquakes, called an earthquake swarm, began on June 12. Within one week, the USGS had already recorded 464 earthquakes.

"This is the highest number of earthquakes at Yellowstone within a single week in the past five years," reported the USGS in a statement released last week.

The majority of the earthquakes were no greater than a magnitude of 1, but the largest reached a magnitude of 4.4, which is the biggest earthquake experienced in Yellowstone since March 2014.

But, thankfully, we don't need to freak out anytime soon. It is extremely unlikely that these swarms will set off the supervolcano. In fact, the USGS sets the probability of the supervolcano erupting in the coming year at 1 in 730,000, and has kept its volcano alert level at green.

"Swarms in Yellowstone are a common occurrence," Jamie Farrell, a research professor at the University of Utah, which is part of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO), told Newsweek.

"On average, Yellowstone sees around 1,500-2,000 earthquakes per year. Of those, 40 to 50 percent occur as part of earthquake swarms."

And while the most recent swarm is larger than average, Farrell says there isn't any evidence that the activity is related to magma moving in the subsurface.

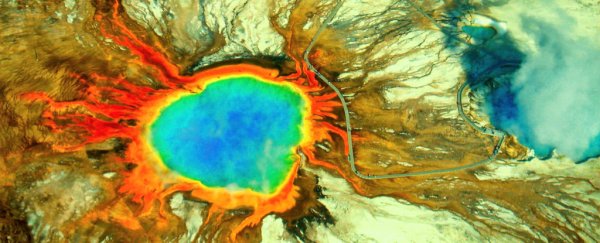

Geologists are constantly monitoring the Yellowstone supervolcano for unusual activity. If the volcano was about to blow, Farrell says they would start seeing increased seismicity, large changes in surface deformation, changes to the hydrothermal system and changes in gas output.

"Typically if we see just one of these things, it doesn't necessarily mean there is an eruption coming. If we start to see changes in all these things, then a red flag may be raised," said Farrell.

The Yellowstone supervolcano doesn't blow very often. In the past two million years, it has only experienced three major eruptions.

But even if it did erupt, Jacob Lowenstern, a scientist in charge of the YVO, says it would be fairly inconsequential.

"If Yellowstone erupts, it's most likely to be a lava flow, as occurred in nearly all the 80 eruptions since the last 'supereruption' 640,000 years ago," he told Newsweek's Hannah Osborne.

"A lava flow would be a big deal at Yellowstone, but would have very little regional or continental effect."

Regardless, Farrell and the rest of the team at the University of Utah assure us they are continuing to monitor the swarm. So there won't be any nasty surprises sneaking up out of Yellowstone anytime soon.