New research shows that the outskirts of our Solar System are littered with many more large comets than has been previously estimated.

These massive icy wanderers can take hundreds or thousands of years to circle our Sun, so it's no wonder that we're still learning more about them. And now astronomers have a fresh perspective on the potential hazards comets may bring.

A team led by researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory used data from the agency's WISE spacecraft to pin down new estimates on comet populations in our corner of the galaxy.

Lately this infrared telescope under the new mission name NEOWISE has been hard at work detecting near-Earth objects, but during its original mission back around 2011 it provided us with complete scans of the entire sky.

And now scientists have dug into that all-sky survey data to find that long-period comets measuring at least 1 kilometre (0.6 miles) across are seven times more abundant than was predicted before. A long-period comet is one that takes at least 200 years or longer to complete a trip around our Sun.

It is thought that most of these long-period comets once emerged from the hypothetical Oort Cloud - the scattered bubble of icy stuff thought to encompass our Solar System even beyond the outer regions of the Kuiper Belt.

"We now know that there are more relatively large chunks of ancient material coming from the Oort Cloud than we thought," says lead researcher James Bauer from the University of Maryland.

"The number of comets speaks to the amount of material left over from the solar system's formation."

Visualisation of Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt / NASA

Visualisation of Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt / NASA

The long-period comets astronomers are detecting today were probably kicked out of the Oort Cloud millions of years ago. An icy chunk could be set on its comet course by a passing molecular cloud, or star, or the tidal forces generated by our galaxy.

"They are the most pristine examples of what the solar system was like when it formed," says Amy Mainzer, NEOWISE principal investigator and one of the researchers on the new study.

The team also discovered that long-period comets are on average two times bigger than the bodies known as 'Jupiter family comets' - chunks of matter whose relatively short 20-year orbits were shaped by our Solar System's mammoth gas giant.

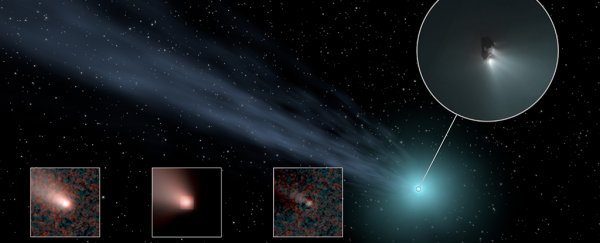

It's hard to measure the size of a comet because these icy balls are typically surrounded by a cloud of gas and dust, obscuring the true size of the comet underneath. But the team cleverly used the WISE infrared data to 'subtract' the dust, ending up with nucleus sizes of the comets themselves.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA/JPL-Caltech

It makes sense that Jupiter family comets are much smaller, because they spend a lot more time in closer proximity to the Sun and thus get stripped of their materials faster.

"Our results mean there's an evolutionary difference between Jupiter family and long-period comets," says Bauer.

Now that we have fresh numbers on the comets swirling through the Solar System, astronomers will be better equipped to predict whether any of these are likely to threaten Earth or bump into other planets.

"Comets travel much faster than asteroids, and some of them are very big," says Mainzer.

"Studies like this will help us define what kind of hazard long-period comets may pose."

The findings have been published in The Astronomical Journal.