There's only one planet we know of in the entire Universe that's capable of hosting life. That's Earth. So, when we search for exoplanets that might host life, it's pretty much what we look for: a rocky exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star at a distance that is neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water on the surface.

To try to figure out the probability of life elsewhere in the Milky Way, one has to start with a reasonable estimate of how many exoplanets are out there that fit such a bill.

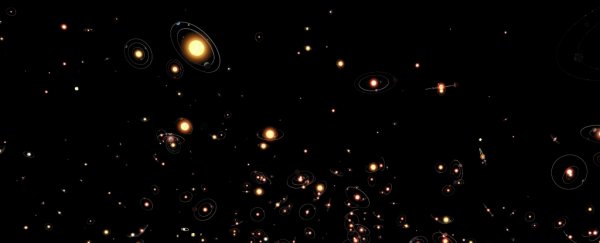

Now, with years of exoplanet-hunting data in the bag, astronomers have made a new calculation and determined there could be as many as 6 billion Earth-like planets orbiting Sun-like stars in the Milky Way.

"My calculations place an upper limit of 0.18 Earth-like planets per G-type star," said astronomer Michelle Kunimoto from the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada. (You may remember that Kunimoto discovered a whopping 17 exoplanets in Kepler data quite recently.)

"Estimating how common different kinds of planets are around different stars can provide important constraints on planet formation and evolution theories, and help optimise future missions dedicated to finding exoplanets."

As our technology improves, the number of planets outside the Solar System we've found has increased in leaps and bounds. To date, we've confirmed 4,164 exoplanets, and the number keeps on growing.

But that's just a drop in the ocean compared to how many planets could be out there. There's an estimated 100 to 400 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, approximately 7 percent of which are like our Sun: G-type main-sequence stars.

However, most of the exoplanets we've found to date are large gas or ice giants, like Jupiter or Neptune. Because it's incredibly hard for us to directly see planets over the very great distances involved, we look at the effects they have on their stars. Smaller, rocky planets like Earth and Mars are harder to find because their effects are much smaller, with a much lower signal-to-noise ratio.

So it's fairly plausible that there are a lot more Earth-like exoplanets in our galaxy than we've spotted so far. To accommodate these missing planets, the team used a technique known as forward modelling to simulate data based on the model's parameters, applying it to a catalogue of 200,000 stars studied by the Kepler planet-hunting spacecraft that operated from 2009 to 2018.

"I started by simulating the full population of exoplanets around the stars Kepler searched," Kunimoto said.

"I marked each planet as 'detected' or 'missed' depending on how likely it was my planet search algorithm would have found them. Then, I compared the detected planets to my actual catalogue of planets. If the simulation produced a close match, then the initial population was likely a good representation of the actual population of planets orbiting those stars."

From this approach, Kunimoto and her UBC colleague, astronomer Jaymie Matthews, could estimate the number of Earth-like planets in the Milky Way. They defined these as between 0.75 and 1.5 times the mass of Earth, orbiting a G-type star at a distance between 0.99 and 1.7 astronomical units (AU, the distance between Earth and the Sun).

At the upper limit of the estimate of G-type stars in the galaxy - a figure that is also very hard to pin down - these calculations returned a maximum of 6 billion of such exoplanets.

The real number, of course, could be much smaller. And there's no guarantee that these planets will have life, or are even habitable; after all, Mars is 1.5 astronomical units from the Sun, and it's so empty of life there aren't even any tumbleweeds.

But the number gives a new tool to work with, both in our search for this class of planets, and for understanding our own existence in this big old chunk of space.

The research has been published in The Astronomical Journal.