Sometimes, the only way to patch up a fracture is to use surgical screws that keep everything in place while the bone is healing.

But sticking a piece of metal inside the body can lead to various complications. Now surgeons have come up with a novel type of screw that's fashioned out of human bone - and it's already being used in several hospitals.

Typical surgical screws are made either out of titanium or stainless steel, and together with metal plates they are a common way to stabilise certain fractures, especially if the broken bone is in a foot or an ankle.

The procedure can lead to a range of complications, though - the body can try to reject the foreign object, causing inflammation and pain, or the patient can have an allergy to the metal, or it can even lead to bacterial infection in the bone.

Worst of all, this type of 'orthopedic hardware' sometimes needs to be removed after the bone has healed, which means a second surgery on top of the first one that got those screws in.

That's why Austrian orthopaedist Klaus Pastl wanted to experiment with new materials for surgical screws, eventually patenting a design for a screw that's made out of… human bone. Because why not?

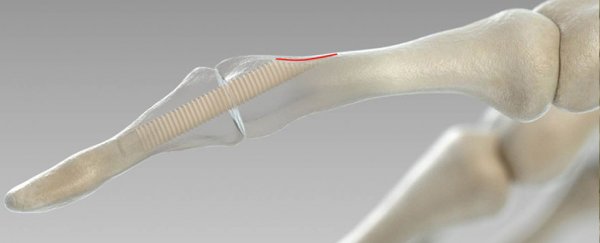

The Shark Screw, as it's called, is made out of the super-sturdy hard middle layer of the femur or thigh bone - the strongest, hardest, and longest bone in the human body.

If you have opted to donate your body to medicine once you die, this offering can include bones as well. In fact, donated material from bone banks is already used in orthopaedic procedures, typically transplants.

In collaboration with researchers from Graz University of Technology (TU Graz), Pastl came up with a unique surgical screw design whittled out of donated bone material.

Even though the first attempts to make screws out of human bone were done in the mid-90s, his design is considered to be the first functional human bone screw graft, and last year it was approved for official use by Austrian and Swiss medical authorities.

Unlike metal, these bone screws don't have to be removed - in fact, after about six weeks, the graft gets incorporated into the patient's own bone tissue, greatly reducing the potential for infection or rejection. According to the team, after a year the transplant can't even be detected on an X-ray.

Currently, the Shark Screw is produced by Pastl's tissue bank startup surgebright, but the researchers are now working on developing specialised screws for foot and jaw surgeries, where these grafts could be especially useful.

"In [jaw] surgery, extremely small screws are necessary, approximately 20 mm long, which have to withstand great stresses," says biomechanics researcher Gerhard Sommer from TU Graz.

"Because relative to size, the jaw muscle is the most powerful muscle in the human body."

The team is now investigating what forces affect bones specifically in feet and the jaw, so that they can customise new human bone grafts for these types of body repairs.

"In general there is a big difference between working with metal screws and screws made of biomaterial," says Sommer.

"The mechanical principles are the same, but we also have to consider that donated bone material shrinks somewhat during sterilisation and two hours after the operation expands again in the body and becomes more elastic.

"For this reason, we are carrying out extensive investigations and tests – both in dry and rehydrated states."

Let's hope their experiments are successful and the Shark Screw catches on in other parts of the world, because it sounds pretty damn awesome.