Last September, a study by UK researchers suggested amyloid pathology, one of the root causes of Alzheimer's, could be transferrable between humans via medical procedures. While we don't yet have proof that this is the case, a new report has just been published that adds further evidence to the claim. Scientists working in Switzerland and Austria have found more cases where amyloid-β proteins were unexpectedly found in human cadavers.

Both studies involve people who have died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease or CJD (the human version of 'mad cow' disease) as a result of surgical grafts taken from other cadavers. While such grafts have now been banned, there are also signs that the seeds of Alzheimer's disease were passed over at the same time - and that could have grave implications for some other hospital procedures that are still in use.

For the time being, no one's suggesting that Alzheimer's is contagious or can be caught from someone else, but these two studies float the possibility that the disease can spread from one human to another through certain types of surgical procedures. That's enough for the report authors to call for more investigation into hospital practices.

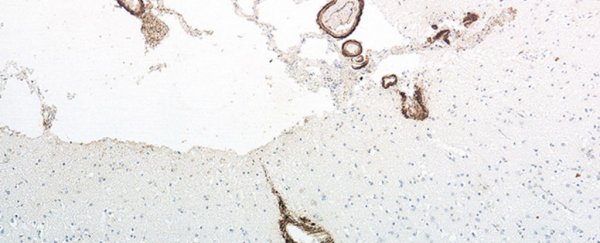

The new study looked at seven people who died of CJD after receiving dura mater (brain membrane) grafts. While none of them had Alzheimer's at the time of their death, five of the brains tested showed signs that the disease might eventually develop: they contained far more of the plaques formed from amyloid-β protein than you would normally expect to find in people of that age (28-63 years old). These plaques could be a trigger for Alzheimer's, research has found.

The 21 control subjects, who died of CJD at similar ages but hadn't been given surgical grafts, didn't show the same amyloid signature.

An earlier procedure that saw similar transmission of possible Alzheimer's triggers, which we reported on late last year, involved hormone extracts taken from deceased humans. "Our results are all consistent," neurologist John Collinge, one of co-authors of last year's paper, told Alison Abbott at Scientific American. "The fact that the new study shows the same pathology emerging after a completely different procedure increases our concern."

As we've mentioned, the procedures that caused this transfer are no longer practiced, but something similar might still be happening in existing treatments. The sticky amyloid-β proteins are not removed by sterilisation and may be present on surgical instruments, for example. One other possibility is that the presence of the proteins were caused by some other underlying condition that the test subjects had in common.

"Nothing is proven yet," said Pierluigi Nicotera, head of the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Bonn, who wasn't involved in thi research. "We need more systematic studies in model organisms to work out if the seeding hypothesis of Alzheimer's is correct."

The new study has been published in the journal Swiss Medical Weekly.