Ecologists studying the effects of climate change have completed a new study that details which US trees will have the toughest time adapting as our world heats up.

The findings suggest that while some species will thrive in a warmer environment, like red hickory and blackjack oak, some species - such as the eastern hemlock, red maple, and eastern white pine - will lose ground, which may eventually lead to them disappearing from their current habitats completely.

But before jumping into the new findings, it's important to note that American forests have had a tough time ever since European settlers arrived on the continent in the 17th century. As developments and cities flourished to life, many forests were levelled and replanted, leaving them fragmented and weak.

"There are hardly any forests in the eastern US that have never been cleared - maybe only a few percent," said team member Patrick Jantz from the Woods Hole Research Centre (WHRC). "And younger, re-growing forests tend to have less structural complexity and different species assemblages."

The US countered this overdevelopment by setting aside land for national parks. While this worked because it protected the lands from human destruction on a physical level, they cannot protect forests from global climate shifts.

Noticing this, the team used climate models to predict what will happen to tree populations inside various parks inside America's Appalachian region.

The team specifically focused on the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (Pennsylvania and New Jersey), Shenandoah National Park (Virginia), and Great Smoky Mountains National Park (North Carolina and Tennessee) – which means these results aren't applicable everywhere. But they do provide some useful insight into which trees will thrive, and which will struggle.

To find out how these areas might change in the future, the researchers used a combination of climate models that assume that carbon dioxide emissions will continue to rise at the same levels they are today, which will take emission rates from 400 parts per million to 1370 parts per million by 2100.

If this happens, temperatures would rise about 0.4 degrees Celsius (0.7 degrees Fahrenheit) every decade up to about 2040. The team also calculated that temperatures will spike a bit, rising 0.7 degrees Celsius (1.2 degrees Fahrenheit) every decade, after 2040, though they do not mention why these rates change that year.

Boiled down, this means that the length of every year's tree growing season will become longer because winters will be warmer and shorter, leading to less frost. It also means that precipitation might drop as well.

"It is entirely possible that precipitation will decrease, which would exacerbate droughts and fire weather," Jantz said. "If, however, precipitation increases substantially, it could enhance growth for many trees in a warmer climate."

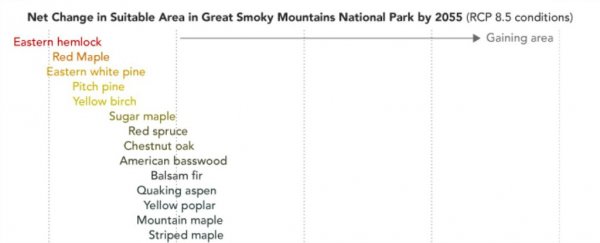

When their model was done crunching the numbers, the researchers created a graph that shows how the resulting conditions would change for 40 different species of trees that are present today inside the Great Smokey Mountains National Park.

WHRC

WHRC

The hardest hit will be those that favour cool and wet habitats such as the eastern hemlock, red maple, and eastern Pine, because the areas where these trees thrive will likely become hotter and, as a result, drier.

On the other hand, some species will actually do quite well, such as post oak, red hickory, and blackjack oak - likely due to them enjoying a hotter, drier climate.

The major downside to all of this is that climate change could wipe out some of these species because they are highly sensitive to climatic shifts in general, which can cause them to not drop seeds or simply not sprout. Plus, unlike other organisms, trees tend to lack the ability to move to a new environment when something befalls the one they call home.

"If you look at the overall suitability of land, a lot of species do well," team member Brendan Rogers said in a report by NASA's Earth Observatory.

"But there are other reasons that trees won't set seed or reach maturity; for instance, the climate might change too quickly, or seeds won't be able to disperse and establish in fragmented land," he added. "It's humbling and disconcerting to see areas where conditions for growth could improve but the trees have little chance of getting there unless there is active management."

Despite the soundness of the results, there is no word if the team's findings, which are detailed in the recently published book Climate Change in Wildlands: Pioneering Approaches to Science and Management, will be published in any peer-reviewed journals, so for now, were taking their word for it.

But it'll hopefully lead to new research and management strategies that will help some of our favourite trees stick around longer.