Researchers in the US have developed tiny, partly functional 'mini-brains' in the laboratory, grown from human cells. These tiny replicas won't only give scientists a better way of testing drugs – they could also help save huge numbers of animals from enduring the hardship of experimental tests.

Official figures suggest more than 800,000 animals are used in experiments every year in the US alone, and that's not counting animals used in agricultural experiments, nor an estimated 100 million mice and rats also used in testing annually. If these mini-brains – which are expected to enter production in 2016 – can replace even a fraction of those numbers, it's a win for animals, and should deliver better results for scientists at the same time.

"Ninety-five percent of drugs that look promising when tested in animal models fail once they are tested in humans at great expense of time and money," said toxicologist Thomas Hartung from Johns Hopkins University. "While rodent models have been useful, we are not 150-pound [68 kilogram] rats. And even though we are not balls of cells either, you can often get much better information from these balls of cells than from rodents."

Hartung and his colleagues created the brains using induced pluripotent stem cells ( iPSCs) – adult cells genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic stem cell-like state, which are then stimulated to grow into brain cells.

The original cells were taken from healthy human adults, but the researchers say the same approach could be used with cells from people with certain genetic traits or diseases for the purposes of specialised pharmaceutical study.

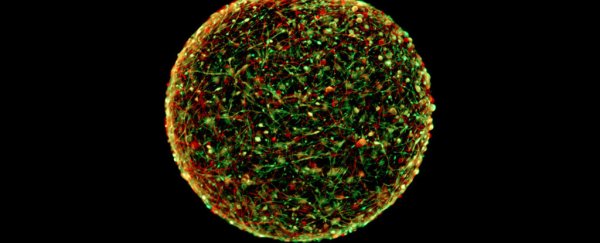

The cells can be grown easily in the lab, with 100 mini-brains fitting inside a single petri dish. They grow to be approximately 350 micrometres in diameter – about the size of the eye of a housefly – and after two months have developed four types of neurons and support cells.

The researchers say that once the mini-brains have grown, they could help scientists study a huge range of conditions, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, autism, viral infections, trauma, and stroke.

While the idea in itself is pretty amazing, it's not the first time we've seen this concept. Last year, scientists at Brown University unveiled a very similar mini-brain model.

But the Johns Hopkins researchers say their own technique – which is in the process of being patented – will imminently enter commercial production. This could see it take off sooner in the scientific marketplace, which in itself could benefit huge amounts of animals.

"We don't have the first brain model nor are we claiming to have the best one," said Hartung. "But this is the most standardised one. And when testing drugs, it is imperative that the cells being studied are as similar as possible to ensure the most comparable and accurate results."

The findings were presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) 2016 Annual Meeting last week.