These days, those of us who have to work for a living (sigh) get our recompense in the form of cash, but it wasn't always this way.

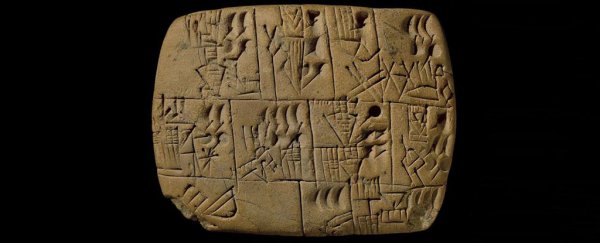

As this approximately 5,000-year-old clay tablet shows, workers in ancient Mesopotamia were actually paid for their toil in daily beer rations – a form of remuneration which seems pretty awesome when you first think about it… and then just keeps on staying awesome the longer you think about it.

Dating back to sometime around 3300 BC, the tablet is one of the earliest known examples of human writing, and was uncovered in what was the city of Uruk, in what we now call Iraq.

As Alison George at New Scientist explains, the tablet displays a human head eating from a bowl – meaning "ration" – and a conical vessel – meaning "beer".

Scratchings across the surface of the tablet denote the amount of beer rations paid to a particular worker, which effectively makes this "the world's oldest known payslip, implying that the concept of worker and employer was familiar 5 millennia ago."

The system of writing seen on the tablet is called cuneiform, and it enabled Mesopotamian administrators to keep accounts on who had been paid and what had been traded, as the BBC explains.

"What's amazing for me is that this is a society where the economy is in its first stages, there is no currency, no money," Gus O'Donnell, former Cabinet Secretary and Head of the British Civil Service, told the BBC in 2010.

"So how do they get around that? Well, the symbols tell us that they have used beer – beer glorious beer, I think that is absolutely tremendous; there is no liquidity crisis here, they are coming up with a different way of getting around the problem of the absence of a currency and at the same time sorting out how to have a functioning state."

Irving Finkel, a curator at the British Museum in charge of these kinds of cuneiform writings, says the Museum is in possession of about 130,000 of these clay-based communications, of which the beer payslip is just one.

"From the outset the writing was done on clay, a most fortunate decision because tablets survive in the ground for millennia even when unbaked," he told the BBC in 2010.

"A cascading waterfall of inscriptions has gradually become available, accounting for more than 3,000 years of history. Only a handful was originally intended to survive long-term; the remainder are more or less ephemeral documents that cover many aspects of life in Mesopotamia, state and private – from beer rations to heroic literature with every kind of document in between."

But while the ancient clay tablet may represent the oldest known evidence of beer-for-labour, it's not the only time in history humans have stuck upon the arrangement. The custom is also in evidence in Ancient Egypt – where pyramid workers were paid 4 to 5 litres per day – and in the Middle Ages, as Annalee Newitz reports for Ars Technica.

Now, if you don't mind, all this talk of beer and hard work has made me just a little bit thirsty.