Digital match-making services have done more than just change how we find our perfect squeeze; they're changing the fundamental nature of our social networks.

According to a pair of researchers investigating online dating, the way we're looking for love (and lust) is connecting communities in completely novel ways, breaking down boundaries and possibly even making for stronger long-term relationships.

It wasn't all that long ago that most relationships would begin with a smile and a handshake, rather than a click or a swipe.

That began to change in the mid-1990s, when websites like Match.com merged traditional lonely-heart classifieds with the convenience of the internet.

Today there's a wide variety of sites and apps to suit your tastes, lifestyle, sexuality, and budget, from Tinder and Bumble for a quick swipe to like, to OKCupid and eHarmony for those who want their wit to show with their words.

Any stigma over online dating has slowly evaporated over the years. 15 percent of Americans admit to having used online dating, and 5 percent of those who are married or committed long-term relationships stating they met their spouse online.

Not only has digital technology made dating easier for romantic hopefuls, the data collected by such sites has been a boon for researchers curious about human mating habits.

But it's clear that the digital revolution hasn't only been shaped by the human appetite for sex and companionship; it's changed the way we form relationships.

Economists Josue Ortega from the University of Essex and Philipp Hergovich from the University of Vienna wanted to know just how the rise of digital match-making has affected the nature of society.

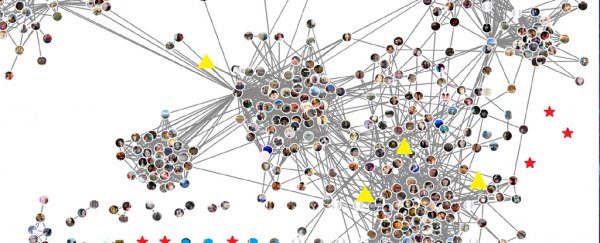

Society can be modelled as a web of interlinked nodes, where individuals are the node and the link describes how well they know one another.

Most people are tightly connected with about a hundred nodes, including close friends and family, and loosely connected with others.

We can trace pathways through relationships to all come to Kevin Bacon – or nearly any other figure on the planet – in surprisingly few steps.

"Those weak ties serve as bridges between our group of close friends and other clustered groups, allowing us to connect to the global community," Ortega and Hergovich told MIT Technology Review.

Even just a few decades ago most new connections were just a jump or two away inside an existing network. A bar, a sporting team, church, or college would typically provide the perfect environment for those first hot sparks.

Not any more.

For heterosexual couples, online dating has risen to second place – just below 'met through friends' – as the context for that first introduction. Among homosexual couples, digital match-making has skyrocketed.

Josue Ortega/University of Essex, Philipp Hergovich/University of Vienna

Josue Ortega/University of Essex, Philipp Hergovich/University of Vienna

And the knock-on effect is profound.

"People who meet online tend to be complete strangers," say the researchers.

As far as networks go, this is like building new highways between towns, rather than taking the local backroads. Just a few random new paths between different node villages can completely change how a network functions.

Take interracial relationships, for example, long held to be a measure of the general social distances within a population.

Once illegal in many states, and long taboo, marriage between different ethnic groups in the US has slowly been on the rise since the mid-20th century.

The increase steepened at the turn of the 21st century in line with the rise in online dating, and then even further as swipe-to-match apps like Tinder went mainstream around 2014 (it launched in late 2012).

While there are almost certainly a variety of influences, the network changes resulting from online dating fits the observations perfectly.

"Our model predicts nearly complete racial integration upon the emergence of online dating, even if the number of partners that individuals meet from newly formed ties is small," say Ortega and Hergovich.

Marriages online were also predicted by the model to be more robust and less likely to end in divorce, a hypothesis which is supported by a study conducted in 2013.

The study is currently available online on the pre-publish website arxiv.com, so it has not completed its full peer-review process just yet.

It can often seem as if the online world reinforces our echo chambers and leads us to become more insular, especially when it comes to social media.

It's nice to have some evidence that the relationships we make online are also breaking down boundaries and making for stronger connections.