Scientists have developed a new technique that allows masses of healthy human neurons to be injected into the brain to replace diseased or damaged nerve cells in patients with brain injuries or degenerative diseases.

The procedure involves injecting minuscule 'scaffolds' loaded with healthy neurons directly into the brain, and while it's so far only been tested in mice, the team says it could be the basis of future treatments for Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease, spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries, and other brain-related conditions.

"The more neurons we can transplant, the more therapeutic benefits you can bring to the disease," says one of the team, Prabhas V. Moghe from Rutgers University. "We want to try to stuff as many neurons as we can in as little space as we can."

How did they do it? The technique involves extracting human pluripotent stem cells (iPS), and converting them into neurons that grow on tiny, three-dimensional scaffolds made from delicate polymer fibres. Each scaffold is about 100 micrometres wide, so roughly the width of a human hair.

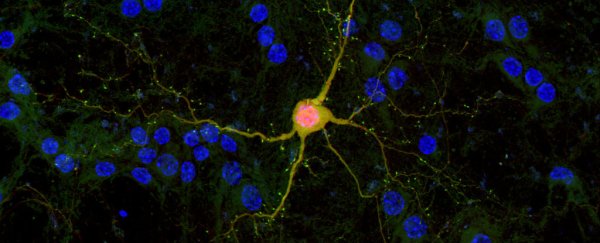

Once the scaffolds are loaded with hundreds of newly formed, healthy neurons, they're injected into the brain to take over operations from deceased or misfunctioning nerve cells. Experiments on mice have shown that, once transplanted, the healthy neurons branch out on their scaffolds and start sending signals to existing neural networks.

"If you can transplant cells in a way that mimics how these cells are already configured in the brain, then you're one step closer to getting the brain to communicate with the cells that you're now transplanting," said Moghe. "In this work, we've done that by providing cues for neurons to rapidly network in 3D."

While this isn't the first time scientists have achieved cell replacement therapy using neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells, this particular technique has ensured that not only do the injected neurons organise themselves and connect with each other and existing neurons, it also saw a 100-fold increase in their survival after transplantation, compared to existing methods.

According to the paper published in Nature Communications, previous techniques have only achieved a cell survival rate of around 1 percent. "These neurons that are transplanted into the brain actually survived quite miraculously well," says Moghe. "In fact, they survived so much better than the gold standard in the field."

We of course have no way of knowing if the technique will work in humans until we actually try it, a) because positive results in mice only very rarely translate to equally positive results in humans, and b) because human brains are far more complex than rodent brains, but the researchers say there's enough potential here to get the procedure ready for human trials.

This will first involve improving the scaffolds themselves so they can hold thousands - or tens of thousands - of neurons, rather than the hundreds they're carrying right now. The team also plans to start testing the technique on mice with Parkinson's to see if it can improve symptoms or maybe even cure the disease.