Scientists in Britain are awaiting a decision by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HEFA) on whether the editing of 'spare' IVF embryos for research purposes is to be made legal. If the bid is approved, a team at the Francis Crick Institute in London says it could begin work straight away, with the first transgenic human embryos in the country expected to arrive within a few weeks or months.

Embryo gene editing is a very controversial topic - some believe it provides an invaluable way to prevent genetic diseases at birth; others think it will eventually lead to 'designer babies' and other unethical uses, as well as affecting the evolution of future generations in ways that can't possibly be predicted. The practice is currently banned in the US, while researchers in China have come under fire for their own early experiments (although only non-viable embryos which couldn't result in births were used).

In the UK, it is permissible to use this gene editing technique for research purposes as long as the embryos are eventually destroyed. As the Francis Crick Institute is the first organisation to apply for a licence under these guidelines, it's something of a test case, which is why the decision is attracting so much interest.

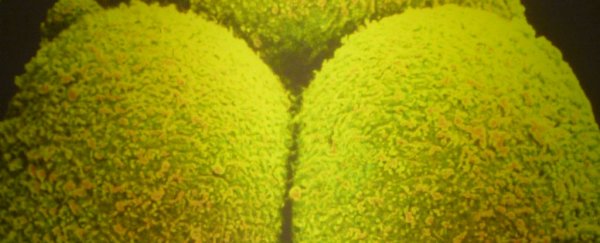

The scientists behind the application want to study the fundamental causes of infertility in embryos over the first seven days of their life - technically known as the blastocyst stage. It will still be forbidden to implant these embryos into the womb, and the researchers say that is not their intention, but if their tests are successful at limiting the chances of a miscarriage, the pressure to allow genetically modified babies will grow.

As we reported back in September when the application was first made, the Francis Crick Institute team wants to use a new gene editing technique called CRISPR/Cas9, which enables scientists to 'cut' out unhealthy DNA and 'paste' in an improved alternative. Since its discovery three years ago, the CRISPR/Cas9 procedure has become more straightforward and less expensive to apply.

The Crick Institute's Robin Lovell-Badge gave Steve Connor at The Independent one example of how gene editing might be used:

"If you found that there were people carrying a specific mutation which meant that their embryos would never implant [in the womb], then you could contemplate using the genome-editing technique to make germline changes which would then allow the offspring of that woman to be able to reproduce without having a problem."

Once the line is crossed, however, there's no going back. David King, of the pressure group Human Genetics Alert, says approval from HEFA would be "the first step on a path that scientists have carefully mapped out towards the legalisation of GM babies".