Millions of years ago, a random genetic accident may have enabled all of modern multicellular life to evolve. A single change was all that was needed to make the jump from single-celled life, like bacteria, to all multicellular life, including humans, scientists reported January 7 in a study published in the journal eLIFE.

The findings not only explain a critical chapter of evolution, they also offer tantalising clues as to what goes awry when cancer cells stop functioning as team players and go back to acting like single-celled organisms, the researchers say.

A single genetic tweak

DNA encodes proteins, the molecules that perform all of the vital jobs in living cells. Mutations are random changes that occur in DNA when a cell divides. While most mutations are fatal to the organism, occasionally they can actually introduce a new piece of cellular machinery that can do something amazing.

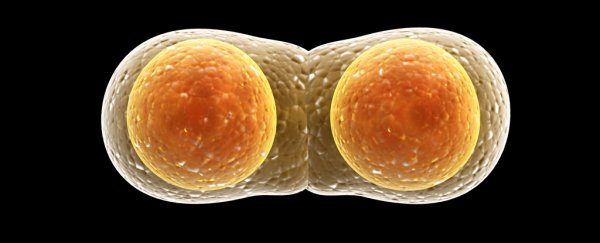

In this case, a mutation allowed single-celled creatures to form a complex with each other, which gave rise to multicellular life.

"Our work suggests that new protein functions can evolve with a very small number of mutations," University of Oregon biochemist Ken Prehoda, who led the study, said in a statement. "In this case, only one was required."

The origin of all animals

To discover this mutation, Prehoda and his colleagues studied a group of microscopic sponge-like creatures called choanoflagellates, which are the closest living single-celled relatives of animals. These tiny, sea-dwelling creatures have a tail, or flagellum, for swimming around, and can live on their own as well as in large colonies.

The researchers used a technique called ancestral protein reconstruction to go 'back in time' to trace the genetic changes that led these single-celled creatures to evolve a protein that is critical for multicellular life.

They found that a mutation in the gene that encoded the animal's tail allowed it to align itself with other cells as part of a colony. This appears to have been the crucial step that allowed single-celled organisms to evolve into multicellular species. A version of this mutation can now be found in all animals, according to the researchers.

This genetic blip "was not solely responsible for the leap out of single-cellular life," The Washington Post notes, but without it, we (and all our multi-celled cousins) might not be around.

And the findings don't just satisfy scientists' curiosity over how we evolved. Cancer is a disease where cells basically 'forget' that they're part of a multicellular organism, Prehoda told The Washington Post, so understanding what makes this happen could lead to better treatments, he said.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: