It's not something many people think about when they drop a few ice cubes into their beverage of choice, but the tiny ice crystals that go into them are not perfect cubes – and no one has ever produced an ice cube formed from perfectly cubic crystals in the lab.

But now researchers have come up with what they say are ice crystals with the highest cubicity yet measured, and it's not for aesthetic purposes. Understanding how these ice crystals can form is a step that could help us understand water molecules and ultimately better predict climate change.

Water molecules in most types of ice, from the ice cubes in your drink to frozen lakes, are based around a hexagonal structure at the microscopic level, but these new crystals were measured as almost 80 percent cubic and a little over 20 percent hexagonal – smashing the previous record by around 10 percent.

"While 80 percent might not sound 'near perfect', most researchers no longer believe that 100 percent pure cubic ice is attainable in the lab or in nature," says lead researcher Barbara Wyslouzil from Ohio State University.

"So the question is, how cubic can we make it with current technology? Previous experiments and computer simulations observed ice that is about 75 percent cubic, but we've exceeded that."

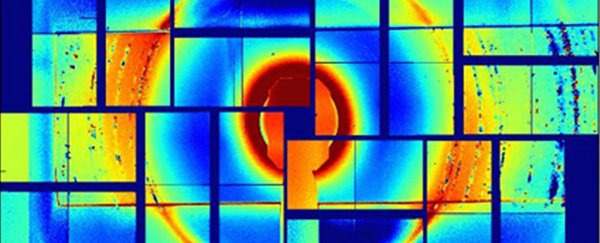

X-ray diffraction image of the ice crystals. Credit: Ohio State University

X-ray diffraction image of the ice crystals. Credit: Ohio State University

To create ice crystals like this, nitrogen and water vapour must be condensed, supercooled and then drawn through tiny nozzles at supersonic speeds. All this is happening on such a tiny scale that you can't see these crystals with the naked eye.

The droplets turned to ice at about -48 degrees Celsius (-54 degrees Fahrenheit) and froze in roughly one millionth of a second. Diffraction patterns created by X-ray lasers were then used to measure the cubicity of the ice crystals.

The fraction of ice that was cubic increased as the coldness of the water used to make the ice increased, and the quickness of the cooling was also crucial. Using very small water droplets enabled the scientists to get the water to a very cold level, but there's still a limit beyond which it's hard to get.

Scientists think perfectly cubic ice may exist in the coldest clouds at the highest altitudes in Earth's atmosphere, creating the light halos that sometimes appear around the Sun.

If we can eventually recreate this ice ourselves, or at least get close to it, we can better understand how sunlight, ice, and clouds interact, leading to better computer models which can be used in climate change research.

Sunshine halos which may be created by cubic ice crystals. Credit: Pixabay

Sunshine halos which may be created by cubic ice crystals. Credit: Pixabay

Part of the problem is we still don't understand how water freezes at the molecular level, and the scientists admit they're not completely sure how they were able to almost hit the 80 percent score on the cubic scale.

"When water freezes slowly, we can think of ice as being built from water molecules the way you build a brick wall, one brick on top of the other," says one of the research team, Claudiu Stan from the PULSE Institute at Stanford University.

"But freezing in high-altitude clouds happens too fast for that to be the case – instead, freezing might be thought as starting from a disordered pile of bricks that hastily rearranges itself to form a brick wall, possibly containing defects or having an unusual arrangement."

Eventually Wyslouzil and her colleagues are hoping to perfect the crystal-making process so they can actually see the ice as it freezes, which should answer some of the questions around how this fundamental process works.

"This kind of crystal-making process is so fast and complex that we need sophisticated equipment just to begin to see what is happening," says Stan.

The research has been published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.