To better understand how our brains work and how to treat the diseases that can cripple them, scientists need a steady supply of grey matter. And that's where the world's largest brain bank - the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Centre (HBTRC) - comes in.

More than 2,000 brain samples are stored here, in shelves that wouldn't look out of place in a school storage room or warehouse. Each brain gets its own plastic tub or bag, and is either frozen or floating in formalin, depending on how it's to be used.

Those potential uses cover just about every research purpose you can think of, such as the study of Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

To investigate the root causes of these diseases in detail, the HBTRC - which is part of McLean Hospital in Massachusetts - needs healthy brains as well as damaged ones, so the differences can be compared.

The centre relies on organ donations, and when a donor dies, the race is on to preserve his or her brain as perfectly as possible.

"We need to have the whole brain intact, with very little damage," assistant director of operations at the HBTRC, Jorge Tejada, told Jessica Hamzelou at New Scientist.

Tejada has worked at the centre for 15 years and has sliced up several hundred human brains in his time - which definitely ranks as one of the more unusual ways of earning a living.

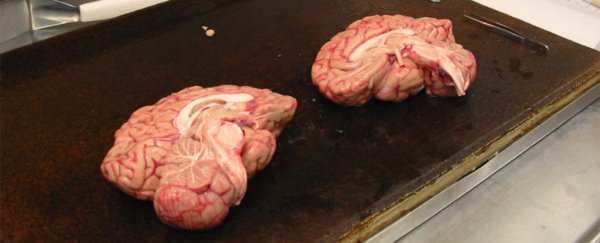

The stored brains. Credit: HBTRC

The stored brains. Credit: HBTRC

Brains can deteriorate quickly after the body dies, so Tejada and his colleagues have a tight 24-hour window to do their thing: obtain permission from the next of kin, and find a pathologist who can extract the brain and put it on ice.

Despite the urgency, it's a very delicate operation because of the softness of the tissue involved.

Once a new brain arrives at the centre, it's weighed and cut in two. One half gets sliced by hand and frozen - which is more suitable for DNA analysis. The other half is put in formalin, which is better for the study of tissue shape and proteins.

The team at the HBTRC also runs a detailed analysis on the brain to test for the cause of death, and look for any viruses that might be present, like HIV or hepatitis.

From there, brain samples are shipped to researchers all over the world when needed, and more than 9,000 brains have passed through the bank since it opened in 1978. Tejada says the hippocampus region - responsible for memory and spatial navigation - is currently in high demand.

While the thought of working among walls of brains might seem a little creepy, Tejada loves his job.

"When you have that brain in your hands you say: 'Oh my God! This is what makes a person think, jump, talk, and do everything,'" Tejada told New Scientist.

"How is it possible that these cells and tissues make such a wonderful machine? That's an amazing part of my work, but I don't have a way to explain that feeling."

You can see the brain donation and storage process in detail on the HBTRC website.