Doctors in Ukraine have announced a world-first, with a 'three-parent' baby being born to an infertile couple.

The child, born on January 5, is the result of new medical techniques that enable a baby to be conceived with DNA from three adults. But the procedure remains controversial, and while it's been approved in the UK as a way of avoiding genetic diseases, this is the first time it's been used as a remedy for infertility.

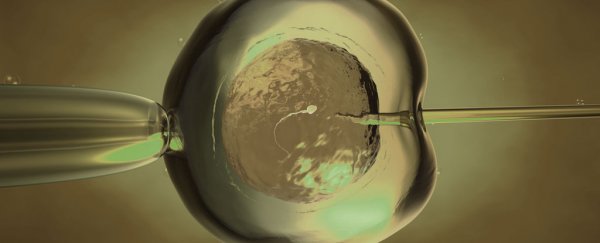

A team led by fertility researcher Valery Zukin at the Nadiya clinic in Kiev helped the baby's parents to conceive by using an in vitro fertilisation (IVF) technique called pronuclear transfer.

In this case, the baby's mother had been trying to have a child for a decade, and had been through four unsuccessful rounds of conventional IVF.

While her eggs were fertilised successfully each time, they stopped growing before they could be implanted in her womb – a condition known as an embryonic arrest.

To get around this happening, Zukin and his team made a hybrid embryo, fertilising the mother's egg with her partner's sperm, and then transferring the resulting pronucleus into an egg from a donor female.

That embryo is then implanted in the mother's womb, resulting in a baby with the genetic identity of both parents, along with the mitochondrial DNA from the donor.

"It's like the opening of a new era," Zukin told Oliver Moody at The Times.

"Before, we could only increase the selection of embryos. But for us this moment opens up the possibility of augmenting embryos."

Mitochondrial donation, which encompasses the pronuclear transfer technique, was legalised in the UK in 2015 for use in a narrow range of circumstances where the mother's mitochondrial DNA is unhealthy, and can lead to children developing genetic diseases.

Then, last year, the procedure was used for the first time to create a 'three-parent baby' in Mexico.

In that case, the mother had Leigh disease, a genetic disorder affecting the nervous system, which she didn't want to pass down through her own mitochondrial DNA.

But the use of the technique as a remedy for infertility complications is decidedly controversial, as safety issues around mitochondrial donation are still being explored, and the prospect of it being carried out in private, unregulated clinics has some scientists concerned.

"If this child appears healthy then that is good news, but we should be sceptical about the merits of mitochondrial donation when it is used as an unorthodox fertility treatment technique," said Sarah Norcross, the director of UK ethics body Progress Educational Trust, in a statement.

"The UK has seen some very thorough reports on the safety and efficacy of mitochondrial donation, but these assessed risk only in relation to patients wishing to avoid transmitting mitochondrial disease to their children. And even then, it was thought prudent to permit the techniques only for judiciously selected patients."

For now, Zukin's team say they have run genetic tests on the baby born in Kiev, and the child appears to be "completely normal".

Beyond that, the doctors seem unconcerned by the controversy, seeing as Ukraine – like Mexico – doesn't have regulations prohibiting these kinds of procedures.

"In Ukraine, the situation is very simple – it's not forbidden," Zukin told Susan Scutti at CNN. "We have not any regulation concerning this."

As has been pointed out, Zukin also serves as vice president of the Ukraine Association for Reproductive Medicine – the organisation that approved the procedure here – so the ethical questions over its usage in this instance are unlikely to go away.

And now Zukin's clinic is expecting another 'three-parent baby' to be born in March, to a second female patient who was infertile for seven years before attempting pronuclear transfer.

While the technique and the publicity around it may give hope to millions of other would-be parents around the world who are struggling to conceive naturally, it's clear scientists at large still have many doubts.

"Pronuclear transfer is highly experimental and has not been properly evaluated or scientifically proven," chairman of the British Fertility Society, Adam Balen, told Michelle Roberts at BBC News.

"We would be extremely cautious about adopting this approach to improve IVF outcomes."