We haven't found any evidence of life on the 3,730 confirmed exoplanets identified to date. Maybe we've just been looking in the wrong place?

Astronomers have come up with new cosmic places that could support live, identifying 121 gas giants that may be orbited by habitable moons.

It's not such a weird idea (although whether the moons in question are as well developed as the Forest Moon of Endor is another matter). NASA is already looking to moons in our Solar System for signs of extraterrestrial life - Enceladus, orbiting the gas giant Saturn, and Jupiter's moon Europa are both thought to have liquid oceans beneath icy crusts.

Meanwhile Jupiter's moon Ganymede has its very own magnetic field, a feature absolutely vital for shielding any life from radiation. And Saturn's moon Titan has a dense atmosphere.

Granted, each are the only known moons in the Solar System that do have those features - but they show that it is absolutely possible for a moon around a gas giant to have a magnetosphere and an atmosphere.

A lot of the work in exoplanet-hunting is focussed on the search for habitable planets - rocky, like Earth; and orbiting in the Goldilocks zone for having liquid water, which is not so far from its host star that water would freeze, but not so close that it would evaporate.

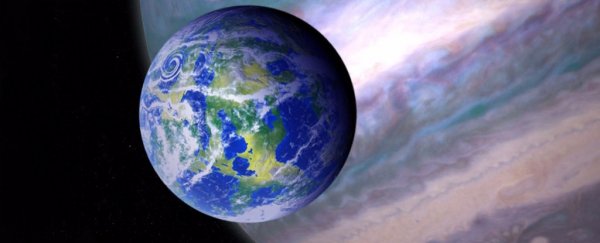

Many of the confirmed exoplanets are gas giants, which would be inhospitable to life as we know it. But, according to researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) and the University of Southern Queensland in Australia, that doesn't mean we need to write them off in the search for life.

"There are currently 175 known moons orbiting the eight planets in our Solar System. While most of these moons orbit Saturn and Jupiter, which are outside the Sun's habitable zone, that may not be the case in other solar systems," said planetary astrophysicist Stephen Kane of UCR.

"Including rocky exomoons in our search for life in space will greatly expand the places we can look."

Together, the researchers have identified 121 gas giants within the Goldilocks zones of their respective stars. If they're anything like the gas giants in our Solar System, each is expected to be orbited by several large moons of its own.

And the scientists believe these moons - if they can be found - could be an excellent place to look for life, since they'd receive radiation not just from the Sun, but the radiation belts of their host planets' magnetospheres.

As an earlier study has pointed out, such moons might have to be at least as big as Mars for their gravity to be able to retain their water.

The part about finding them could be the tricky one. Currently, astronomers use two main methods for finding exoplanets: observing the light of a star dimming regularly over time, as the orbiting planet passes between us and it; or observing the very, very faint Doppler shift as the gravitational tug the planet exerts on the star moves it ever-so-slightly towards us and away from us.

Both methods rely on light, which planets don't usually emit, so hunting down these moons is probably going to be a job for future telescopes, rather than any technology we currently have.

But identifying places to look is an early step in getting that ball rolling.

"Now that we have created a database of the known giant planets in the habitable zone of their star, observations of the best candidates for hosting potential exomoons will be made to help refine the expected exomoon properties," said Michelle Hill of USQ.

"Our follow-up studies will help inform future telescope design so that we can detect these moons, study their properties, and look for signs of life."

The team's paper has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal, and can be read on arXiv.