When scientists uncover bones and other hard objects from the ground, they can sometimes find scraps of organic material attached. But nothing we've found comes close to the age of proteins recently discovered on a dinosaur fossil thought to date back 195 million years.

That's around 100 million years older than fragments of collagen found in the thigh bone of a hadrosaur in 2009, and it could give us a unique look back at the biology of other dinosaurs that wandered the Earth at the time.

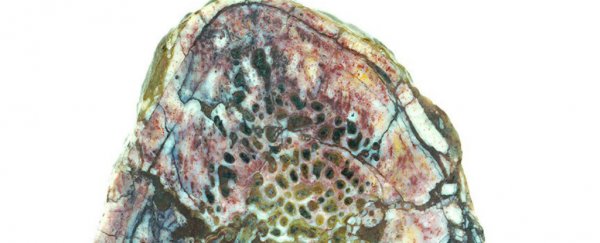

The discovery was made by researchers at the University of Toronto within a rib of a Lufengosaurus dinosaur, a long-necked herbivore that roamed across what's now south-western China during the Early Jurassic period.

"These proteins are the building blocks of animal soft tissues, and it's exciting to understand how they have been preserved," says one of the research team, palaeontologist Robert Reisz.

With the help of colleagues in China and Taiwan, researchers used a synchrotron machine to analyse fossil samples.

The device uses infrared spectroscopy, or targeted beams of light, to identify materials - in this case collagen and iron-rich proteins - without having to risk contaminating the samples.

Robert Reisz

Robert Reisz

Previous collagen discoveries of this kind required dissolving the rest of the fossilised bone away, and the team behind the latest research says its non-invasive approach could open the way to finding even more organic remains in the future.

To find any kind of soft tissue material is very rare though, as it normally decays naturally in the ground, leaving only the bones behind.

Scientists still aren't sure why some proteins and collagen are able to survive for so long, but in this case the researchers think the blood vessels helped to form a "closed micro-sized chamber" that isolated the material.

The researchers suggest that small, iron rich particles left over from blood flowing through the rib bones might have been the source of the haematite which bound to the proteins and helped protect them against the ravages of time.

One of the insights the new find might give us is how dinosaurs evolved into the species of birds we still see on Earth today, which is thought to have happened over the course of just 10 million years – a very short timespan in evolutionary terms.

In the meantime, Reiz says the synchrotron technique has "great future potential", and should be able to pick up organic material even when there's only a minuscule amount of it left behind.

That said, don't expect a Jurassic Park-style theme park anytime soon - these scraps of matter aren't enough to provide dinosaur DNA, which is thought to decay naturally within half a century.

Some experts, including Mary Schweitzer from North Carolina State University, say the current tests are too limited in scope for us to know conclusively what we're dealing with on these bones, saying that further analysis is required.

Others, including Stephen Brusatte from the University of Edinburgh in the UK, think the evidence is already strong enough. Neither Schweitzer nor Brusatte were directly involved in the research.

"To find proteins in a 195-million-year-old dinosaur fossil is a startling discovery," Brusatte told the BBC.

"It almost sounds too good to be true, but this team has used every method at their disposal to verify their discovery, and it seems to hold up."

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.