After more than two years of analysis, the oldest complete ice core has served up a reliable snapshot of our planet's atmosphere from nearly 2 million years ago. And the results are not what many expected.

We know that roughly 1 million years ago, the cycle of Earth's ice ages suddenly shifted, with deeper and longer freezes occurring only every 100,000 years, instead of once every 40,000 years.

Nothing in our planet's orbit could explain the 'abrupt' change, known as the Mid-Pleistocene transition (MPT), and with few other explanations, some hypothesised there must have been a long-term decline in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, cooling the planet to a new threshold.

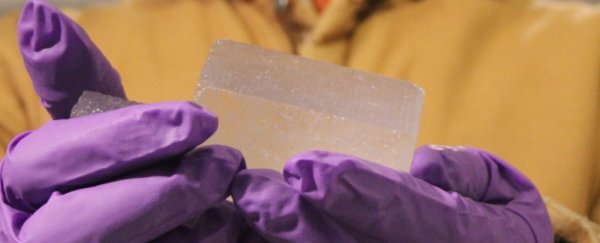

Ancient air bubbles trapped in the Antarctic ice sheet have now revealed a somewhat different picture. Dating back roughly 1.5 million years, these tiny doses of our ancient atmosphere contain "amazingly low" CO2 levels, according to paleoclimatologist Yige Zhang from Texas A&M University, who was not involved in the study and who told Science Magazine he found the results "quite interesting".

These are the first direct observations of atmospheric greenhouse gases before the ice ages on Earth began to grow longer, and they suggest something other than a long-term decline in CO2 was at play to shift our planet's entire ice age cycle.

The oldest sample of ice we could test for CO2 levels previous to this new core was a 'mere' 800,000 years old; other estimates based on the chemistry of Earth's sediments are only useful as a proxy for greenhouse gas levels - they're not useless, but more verification is necessary.

The new ice analysis, which used more precise measurements than before, has revealed that "although CO2 levels during glacials stayed well above the lows that occurred during the deep glacials of the past 800,000 years, the maximum CO2 concentrations during interglacials did not decline," Earth scientist Eric Wolff from the University of Cambridge writes in a review of the research.

"One of the important results of this study is to show that carbon dioxide is linked to temperature in this earlier time period," says atmospheric scientist Ed Brook from Oregon State University.

"That's an important baseline for understanding climate science and calibrating models that predict future change."

In other words, the relationship between CO2 levels and Antarctic temperature hasn't changed much over this time span. And the lower CO2 levels during ice ages are probably just a consequence of the shorter glacial periods that occurred before the MPT.

In fact, the authors found the lowest levels of CO2 didn't show up for the first 40,000 years after the MPT occurred.

"Our findings appear to be inconsistent with hypotheses that attribute the transition into the 100k world to a long-term decline in both interglacial and glacial atmospheric CO2," they write.

In his review of the research, Wolff commended the researchers on their precise estimates and "tantalising" snapshots. But he argues a more "complete, undisturbed time series" is needed to put CO2 levels in context.

Luckily for us, the ancient ice core, which was found in Antarctica's Allan Hills, may soon have company. Researchers say the ice sheet here dates back 2.7 million years and maybe even longer.

Given how much the ice has shifted in this region, any new cores we dig up will probably come in discontinuous sections, but their information may help us piece together at least some of the secrets of our planet's mysterious past.

"We don't know the age limit in this area," Brook says. "It could be much older in some places. That's why we're going back. Pushing beyond two million years would be pretty amazing."

The study was published in Nature.