However badly your day is going, spare a thought for the ancient sea cow that's the subject of newly published research from an international research team.

Dragged by a crocodile before its body was later chewed on by a shark some 20 million years ago, it wouldn't have been a pleasant end for the dugong. But a study of its remains gives modern day experts a fascinating insight into the marine food chain of the Early to Middle Miocene epoch – which, it seems, worked in a similar way to how it does now.

"Today, often when we observe a predator in the wild, we find the carcass of prey which demonstrates its function as a food source for other animals too, but fossil records of this are rarer," says paleontologist Aldo Benites-Palomino, from the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

"We have been unsure as to which animals would serve this purpose as a food source for multiple predators."

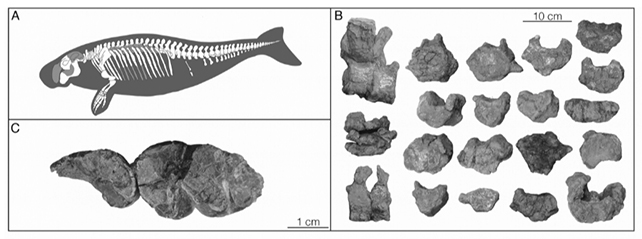

The story starts with the discovery of some unusual rocks by a local farmer, south of the city of Coro, in northern Venezuela. When the researchers were called in, they found the minerals contained parts of a skeleton fossil, including a section of a skull and 18 different vertebrae.

Analysis showed that they were left by an individual from the extinct sea cow genus Culebratherium which met a most unfortunate end.

A study of bite marks found on the fossils helped the researchers reconstruct its final hours. It seems to have been attacked by a crocodile that tore into the sea cow, and quite possibly took it down in a death roll. The team also found marks across the skeleton consistent in shape and size with the teeth of an extinct tiger shark (Galeocerdo sp), apparently scavenging meat from the dead or dying animal. They even confirmed the shark species – G. aduncus – from the tooth it left behind in the sea cow's neck.

It appears that once the crocodile had had its fill, then another carnivore came along to pick at whatever was left.

By analyzing the sediment around the area where the remains were discovered – well away from previous fossil finds in the region – the researchers were able to date the fossil back around 20 million years.

"Our findings constitute one of the few records documenting multiple predators over a single prey, and as such provide a glimpse of food chain networks in this region during the Miocene," says Benites-Palomino.

Being able to build up such a complete picture of this sea cow's demise is testament to the hard work of the research team: in total, several months of effort were involved in identifying the fossil and determining what had happened to it.

"Evidence of trophic interactions are not scarce in the fossil record, yet these are mostly represented by fragmentary fossils exhibiting marks of ambiguous significance," the researchers write in their published paper.

"Differentiating between marks of active predation and scavenging events is therefore often challenging."

The research has been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.