Dozens of broken pieces of pottery dating between 2,000 and 3,000 years old have been unearthed on a windswept island on the Great Barrier Reef – the oldest pottery ever discovered in Australia.

The remnants, found less than a meter below the surface by Traditional Owners and archeologists, mark a millennia-long practice of First Nations people making ceramics on Jiigurru (Lizard Island).

Made from locally sourced clay and sand, the pottery was fired thousands of years before British colonists invaded Australia in 1788, at a time when other island communities in the region were also making ceramics.

"These findings not only open a new chapter in Australian, Melanesian, and Pacific archaeology but also challenge colonialist stereotypes by highlighting the complexity and innovation of Aboriginal communities," says senior author Ian McNiven, an archeologist from Monash University in Australia.

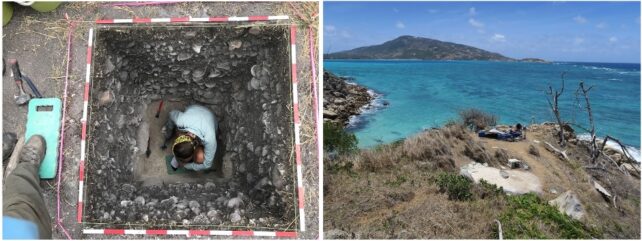

Working over two years in the baking sun, covered in salt, sea spray, and crusted sweat, the team of researchers and Dingaal and Ngurrumungu Aboriginal community members steadily excavated a shell midden some 2.4 meters (nearly 8 feet) deep to find pieces of pottery among the remains of shellfish, fish and turtle bones, and charred plant materials.

Broken pottery pieces, otherwise known as sherds, have been found on Jiigurru before, way back in 2006, in an intertidal lagoon. But archeologists didn't know how old they were or who made them. Daily tides had eroded the sherds, and dating was inconclusive, leaving researchers with nothing more than a tantalizing hunch that locally made pottery might one day be found on Jiigurru.

McNiven and the team kept digging, failing to find any other signs of pottery in another nearby shell midden dating back 4,000 years.

Then, in 2017, their luck changed. An archaeology student on the team found the first piece of pottery, just 40 centimeters below the surface.

"I remember Ian and I looking at each other across the pit in amazement," James Cook University archaeologist Sean Ulm told ScienceAlert.

"We stopped the excavation and documented the find very carefully. There were deep discussions long into the night about what the finding might mean and how we should progress the excavation from here."

Radiocarbon dating revealed the deepest layers of the excavated midden had been deposited some 6,510 to 5,790 years ago, making Jiigurru the earliest offshore island occupied on the northern Great Barrier Reef.

Occupation of the site dramatically increased around 3,000 years ago, the researchers found, when marine shells started piling up and the earliest ceramics found in the midden fell to their final resting place.

For another thousand years or so, until about 2,000 years ago, ceramics were made, used and discarded by local people, the team's dating suggests. This makes the Jiigurru ceramics the oldest pottery ever discovered in Australia.

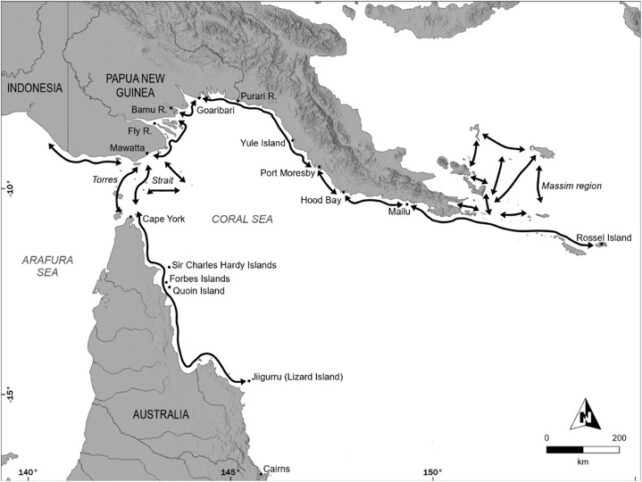

They are several hundred years older than two dozen pottery sherds uncovered on an island further north in the Torres Strait, between the tip of the Australian mainland, Cape York, and Papua New Guinea, which McNiven and colleagues described in 2006.

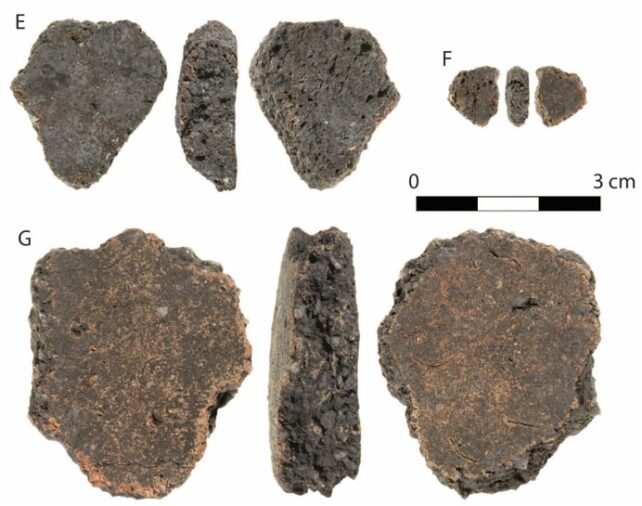

The Jiigurru ceramics were also locally made. Analyses revealed the sherds were made of clay and contain quartz, calcareous sand and feldspar similar to beach sands sampled on the island. The researchers also determined the fragments were from small, thin-walled vessels that were less likely to crack than thicker pots and lighter to transport.

"We think that the ancestors of contemporary Traditional Owners [of Jiigurru] were engaged in a very widespread trading system" that included cultural exchanges with pottery-making communities of Papua New Guinea," says Ulm.

The people of Jiigurru were seafarers who "knew how to make pottery, and made it locally," Ulm explains, likely swapping technological know-how, goods and ideas with other island communities.

That knowledge of pottery-making has since been lost, either for reasons unknown prior to British colonization or with the displacement and fragmentation of communities.

But finding these expertly made ceramics baked thousands of years ago could help local communities revitalize the practice and protect Jiigurru into the future, by providing tangible evidence of their occupation of the island otherwise recorded in oral histories.

The excavation was the first time the local Indigenous people of Jiigurru had worked with archeologists to reconnect with the history embedded within their ancestral lands.

"Every bit of knowledge we gain helps us tell the story of Country," Ngurrumungu Elder Brian Cobus said in a statement. "Research projects like this help us all to understand Country better and help us to understand how to look after Country."

The research has been published in Quaternary Science Reviews.