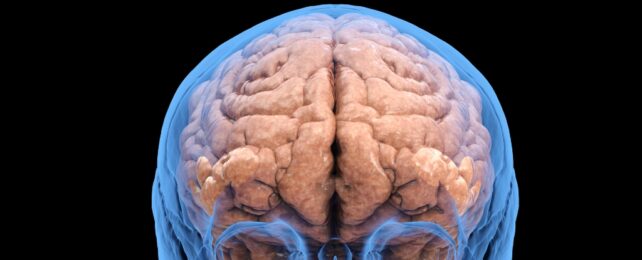

In encouraging news for people recovering from alcohol use disorder, new research demonstrates how quickly the brain can repair its structure once drinking ceases.

People with alcohol use disorder (AUD) tend to have thinning in regions of their cortex; the wrinkled outer layer to the brain critical to so many higher order cognitive functions. The US study found those who quit drinking gain cortical thickness over time, faster in the first month and continuing over 7.3 months, at which point thickness is comparable to those without AUD.

Previous research had shown that some regions may recover when someone stops drinking, but it was unclear much or how quickly recovery occurs.

"The few longitudinal studies investigating cortical thickness changes during abstinence are limited to the first month of sobriety," writes the team, led by psychiatrist and behavioral scientist Timothy Durazzo from Stanford University.

"However, the extent of regional cortical thickness recovery over an extended period of abstinence (e.g., greater than 6 months) is unknown."

An estimated 16 million people in the US suffer from AUD. It's a major public health issue, and understanding this complex disorder is important for treatment, prevention, and reducing stigma.

Alterations to brain structure and function during chronic alcohol use can make it tough for people to stop drinking, despite their best intentions. For instance, the prefrontal cortex – an area involved in planning and decision-making – may become less active, making it harder for people with AUD to make healthy decisions.

Durazzo and colleagues also examined how some health conditions, smoking history, psychiatric conditions, and substance use disorders affect longer-term cortical thickness changes in people recovering from AUD.

Altogether, 88 people with AUD participated in the study, undergoing brain scans at approximately 1 week, 1 month, and 7.3 months of abstinence. Some participants joined at the 1 month mark, meaning 23 individals didn't have scans taken at 1 week, and only 40 of the total 88 continued to abstain from alcohol for the full period.

They also looked at 45 people who had never had AUD, measuring their cortical thickness at baseline and again about 9 months later to confirm the areas that were measured stayed the same.

A type of magnetic resonance imaging ( MRI) that's particularly useful for getting clear pictures of the body's internal structure was used to observe the participants' brains. The researchers recorded cortical thickness for 34 regions, averaging the measurement across the brain's left and right hemispheres.

Recovery of thickness in those with AUD after 7.3 months without alcohol was quite widespread. It was enough to be statistically significant in 25 of the 34 regions, and 24 of these were considered statistically equivalent in thickness to controls.

All 34 cortical regions that Durazzo and his team looked at saw a faster rate of thickness change in AUD participants from 1 week to 1 month after quitting, than from 1 month to 7.3 months.

Cortical thickening happened more slowly in some parts of the brains of people with AUD who also had high blood pressure or high cholesterol. The same was true for people with AUD who were current smokers.

No significant relationships were found between cortical thickness changes and current substance abuse (including drugs other than alcohol), or psychiatric disorders, or past cigarette smoking. So quitting smoking might also contribute to recovery of cortical thickness.

These results provide encouragement and a new understanding of brain recovery after quitting alcohol, though due to the small sample size and lack of diversity, they may not be generalizable. Also, it's important to note these findings don't indicate whether the changes had any effect on brain function.

"Larger longitudinal studies are required to examine the neurocognitive and psychosocial correlates of cortical thickness recovery during sustained abstinence in AUD," the team writes.

The authors also point out that variables they didn't account for, such as genetics, physical activity, and people's liver and lung health, could have affected their findings.

"This data provides clinically relevant information on the beneficial effects of sustained sobriety on human brain morphology," the authors conclude, "and reinforces the adaptive effects of abstinence-based recovery in AUD."

The study has been published in Alcohol.