There's a rare genetic disease that causes fragile skin all over the body to painfully blister at the slightest touch. It has no known cure. But now a workaround developed by scientists could potentially transform the lives of thousands with the condition.

Researchers are reporting the successful treatment of a severe case of junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB), where mutations cause chronic wounds to the skin. In this case, doctors were able to reconstruct 80 percent of a boy's epidermis with genetically modified skin cells.

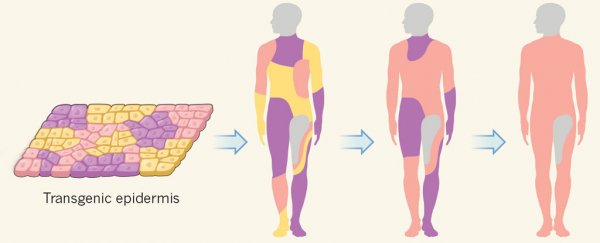

The technique involves attaching genetically modified skin grafts to the dermis, the tissue underlying the external layer of skin. The same method has been used previously in two patients with epidermolysis bullosa skin lesions, but in those cases only small skin patches were rebuilt.

Here, the team, led by stem cell researcher Michele De Luca from the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy, says their technique can bring about "life-saving regeneration of virtually the entire epidermis".

(De Luca et al/Nature)

(De Luca et al/Nature)

The patient in question was a seven-year-old boy who was admitted to a hospital burns unit in Germany in June 2015 with severe blisters and lesions that ultimately saw him lose 80 percent of the skin covering his body.

With all remedial therapies failing, his parents consented to what may have been the only chance to save their son's life: rebuilding his lost epidermis piece by piece.

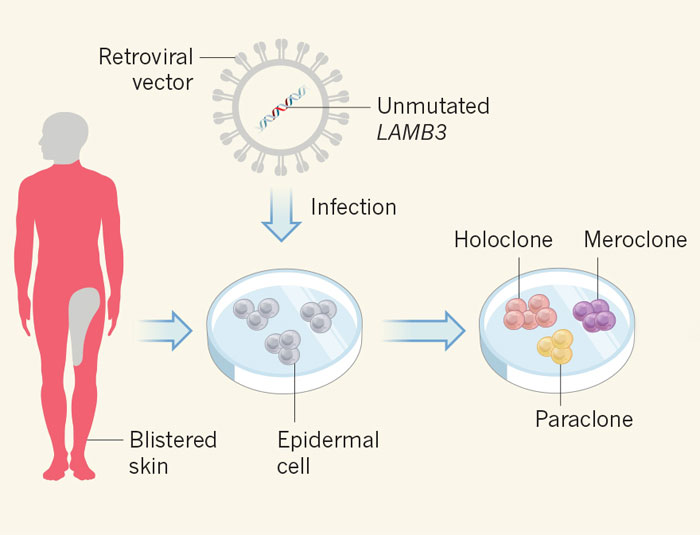

The researchers took skin cells from a non-blistering area of the boy's body, and used them to establish protein cultures that were genetically modified to be free of the mutation responsible for the boy's condition – in this case, a variant of a gene called LAMB3.

The team grew these cultures into a series of transgenic epidermal grafts, which over the course of three operations replaced the boy's lost skin with a healthy new epidermis.

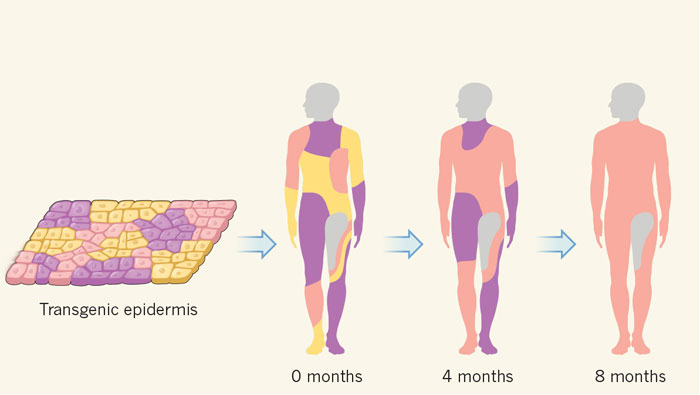

In follow-up examinations 21 months after the final surgery, the patient seemed to have made a full recovery, with his new skin healthy and free of blisters, demonstrating the usual resistance to stress that's not seen in patients with JEB.

(De Luca et al/Nature)

(De Luca et al/Nature)

"The patient was discharged in February 2016," the researchers write in their paper.

"His epidermis is currently stable and robust, and does not blister, itch, or require ointment or medications."

It's an amazing and uplifting turnaround for a child whose short life may have ended without this kind of remarkable intervention – although the team acknowledges such extensive treatments wouldn't usually be necessary, even if they are now scientifically possible.

"It can be argued that the patient's clinical picture (massive epidermal loss, critical conditions, poor short-term prognosis) was unusual and our aggressive surgery (mandatory for this patient) unthinkable for the clinical course of most patients with epidermolysis bullosa," they explain.

"However, progressive replacement of diseased epidermis can be attained in multiple, less-invasive surgical interventions on more limited body areas."

More follow-ups will be needed to make sure the boy's skin stays healthy as he gets older, but with as many as 500,000 people around the world estimated to be affected by some form of epidermolysis bullosa, this is a really promising new beginning.

The findings are reported in Nature.