A new discovery of stone tools and other evidence has revealed that hominins - our pre-human relatives - were in South East Asia hundreds of thousands of years earlier than we thought.

Found in the Philippines, the 57 stone tools and an almost complete rhinoceros skeleton showing signs of having been butchered, date back 709,000 years.

Previously, the earliest evidence for hominin habitation in the region, a river floodplain on the northern island of Luzon, had been a small foot bone found in Callao Cave. It's only 67,000 years old.

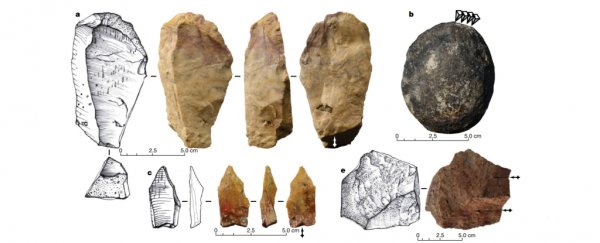

The tools found consist of 49 sharp-edge stone flakes, six cores - the stones from which the flakes are hammered - and two possible hammer stones. In addition, the site yielded a collection of skeletons: a stegodon, brown deer, freshwater turtle, and monitor lizard.

The rhinoceros skeleton was very interesting. Several of the bones had cut marks consistent with butchering, and the humerus bones seemed to have been hit with a hammer stone, possibly to access the rich marrow inside.

The tools weren't made by humans - our oldest evidence of Homo sapiens is from about 300,000 years ago - but by a close ancestor. And their presence means we need to reconsider how humans and hominins spread through South East Asia.

Archaeologist Gerrit van den Bergh from the University of Wollongong in Australia says that hominins most likely spread through the region in several waves throughout the millennia.

He also believes that they probably travelled from north to south from China and Taiwan, rather than west to East from Borneo or Palawan through Indonesia, using the ocean currents and settling as they went.

Eventually this migration could have landed on the Indonesian island of Flores to give rise to Homo floresiensis, also known as the "hobbit" for its small stature.

Evidence of hominins dating back 700,000 years has been found on the Indonesian island of Java. In addition, Homo floresiensis ancestors have been found on Flores from around the same time. Both of these finds are consistent with the new migration hypothesis.

Previously, it had been thought that hominins didn't have boats, and therefore couldn't have travelled by water to reach Luzon and the other islands of Wallacea, the group of islands separated from mainland Australia and Asia by deep oceans.

But the north-to-south migration hypothesis is supported by another fossil record: that of animals.

"If you look at the fossil and recent faunas you see that there is an impoverishment as you go from north to south. On Luzon you find fossils of stegodons, elephants, giant rats, rhino, deer, large reptiles and a type of water buffalo.

"On Sulawesi, the fossil fauna is already impoverished; there's no evidence of rhinos or deer ever entering there. Then on Flores, you only had stegodons, Komodo dragons, humans and giant rats, that's all," van den Bergh said.

"If animals did reach these islands by chance, by entering the sea and following the currents south, then you would expect the further south you go the fewer species you would find - and that's what we see."

If the animals didn't have boats, the humans needn't have either. However, they could have had rafts, used for fishing, or been caught up in debris and carried out to sea by tsunamis, which are relatively common in the area.

Who these hominins were is unknown, and will probably remain so without their bones to study. They could have been the ancestors of the owner of that foot bone hundreds of thousands of years later; they could have been Luzon's version of Homo floresiensis; or they could have been a different group, perhaps even the mysterious Denisovans.

But the discovery has archaeologists excited to keep digging to see what else they can find.

"There's a lot of focus again in the islands of South East Asia because they are places where you find natural experiments in hominin evolution. That's what makes Flores unique, and now Luzon is another place we can start looking for fossil evidence," van den Bergh said.

"On Flores, we're pretty certain they arrived about 1 million years ago based on stone tool evidence, but we don't know when hominins first arrived on Luzon. Now we can go looking in older strata and see if we can find more artefacts, or even better, fossil evidence."

The research has been published in the journal Nature.