Analyzing two decades of satellite imagery, researchers from the US and UK have found Earth's oceans are getting greener, potentially reflecting the impact climate change is having on phytoplankton populations as the world warms.

The tiny microbes, including plant-like algae, use green chlorophyll to photosynthesize. So the greater their numbers, the greener their habitat becomes.

As appealing as a greener world might sound, a surge in phytoplankton concentrations is likely to have numerous knock-on effects on ocean ecosystems.

We are already witnessing severe short term impacts of heat-induced increases in phytoplankton. Their sudden population booms rob their surroundings of oxygen, creating hypoxic dead zones that not all animals can escape.

But there are longer term consequences too, which we are yet to understand.

One of the open questions around these long term changes is how much data is sufficient to spot them, with previous estimates suggesting that three decades of observations would be required to detect shifts in ocean ecosystems.

Here, the team of researchers demonstrated around 20 years of data from the MODIS-Aqua satellite is enough, meaning we can observe, understand, and react to climate change more quickly.

That faster turnaround is thanks to remote sensing reflectance, which refers to snapshots of ocean color based on reflected light. Processing these snapshots is in some ways more straightforward than trying to measure phytoplankton populations using other methods, such as chlorophyll estimates.

That's not to say phytoplankton is the only reason the ocean could be getting greener, as the researchers admit. However, their analysis closely matches an advanced model predicting how ocean ecosystems might be responding to climate change.

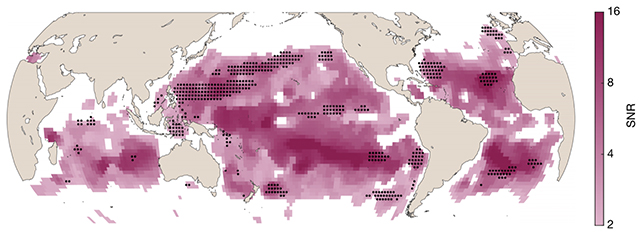

"Remote sensing reflectance, and thus surface-ocean ecology, has changed significantly over a large fraction of the ocean in the past 20 years," the researchers write in their published paper.

The greening of the ocean was particularly noticeable around the equator, the study reports.

As phytoplankton absorbs CO2, their increased numbers could be seen as a valuable carbon sink, making the link more complex than first appears.

But since they can alter so much of their environment – including temperature, nutrient availability, and light levels in the water, and are the foundation of the marine food chain — the increase in numbers is also likely to cause widespread significant changes to resources like conservation zones and fisheries.

This study doesn't dive into those consequences in too much depth, but whatever this ocean greening means, it seems as though it's already happening – and thanks to the latest research, they've come to light ten years ahead of time.

"Altogether, these results suggest that the effects of climate change are already being felt in surface marine microbial ecosystems, but have not yet been detected," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Nature.