The human body is cloaked in skin, a protective layer that shields our insides from external threats. But there are a few weak spots and a few openings that need extra defenses.

In the eye, for instance, specialized immune cells patrol for trespassers we cannot see but could slip in. However, scientists have just realized these immune cells are not quite what they thought they were.

"Until now, these cells were mistakenly classified as dendritic cells based on static imaging," explains Scott Mueller, an immunologist at the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia.

Dendritic cells are scouts that present recognizable tags called antigens, gathered from intruding cells, viruses, or other foreign material, to other immune cells called T cells. These T cells, part of the body's adaptive immune system, mount a response if the antigens don't match the body's own and remember the intruders for next time.

"By combining our newly developed imaging technique with other advanced analytical approaches, we were able to discover that a significant number of cells at the surface of the healthy cornea are actually T cells," Mueller says.

The cornea is the transparent covering of the eye through which we see. Its curvature accounts for two-thirds of the eye's optical power. To preserve this vision, immune responses such as inflammation must be tightly controlled in the cornea.

Based on animal studies published last year, Mueller and colleagues suspected that many of the cornea's resident immune cells were actually T cells. They had seen how these T cells protected against eye infections in mice and wondered if the same was true in humans.

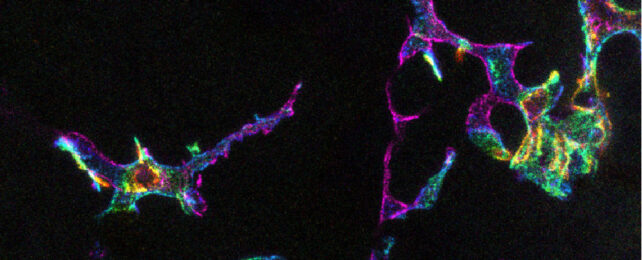

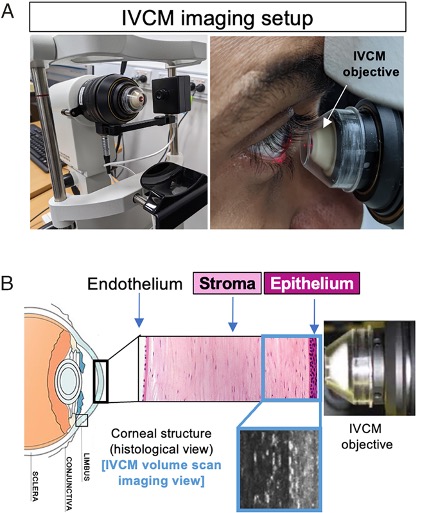

To take a look, they used an imaging technique called functional in vivo confocal microscopy, which allows researchers to visualize living tissue at cellular levels and track their movements in time-lapse videos (rather than looking at slices of preserved tissue).

Imaging healthy human corneas in 16 young adults revealed T cells jostling about on high alert, interacting with dendritic cells and nerves in the cornea's outermost layer, the corneal epithelium.

"Imaging deeper into the corneal stroma, we show that crawling macrophages and rare motile T cells patrol the tissue," the team writes in their published paper.

The findings expand our understanding of the types of immune cells residing in the cornea, protecting us from pathogens, and the researchers also showed how T cells specifically respond to different stimuli.

The team captured how the eye's immune cells responded to short-term contact lens wear and in individuals with allergic eye disease and how drug treatments helped modulate the cells' behavior.

"Because this new technique involves non-invasive, time-lapse imaging of the human cornea, [it] could be used in clinics directly to assess immune responses and ocular health," says ocular immunologist Holly Chinnery of the University of Melbourne.

Of course, the technique will need further validation before clinical use.

Researchers have, however, used similar techniques before to monitor microstructural changes in the cornea after cataract surgery in people with diabetes who are prone to developing cataracts, cloudy occlusions that form in the lens of the eye.

Understanding how immune cells help preserve (or possibly impair) eye function is important because corneal infections or cataract surgery in one eye can impact the other – with inflammation spreading between the two ocular surfaces and nerve cells.

The study has been published in PNAS.