An international effort to revive an ancient roundworm, frozen in Siberian permafrost for millennia, has unleashed a lifeform even older than scientists once thought.

In 2018, several resurrected nematodes, of the genus Panagrolaimus, were dated to around 32,000 years old. But now, more precise radiocarbon dating suggests these soil worms have remained 'dead awake' in parts of Siberia since at least the late Pleistocene, around 46,000 years ago.

If correct, the record absolutely smashes the longest known state of extreme inactivity observed among animal life, a phenomenon known as cryptobiosis.

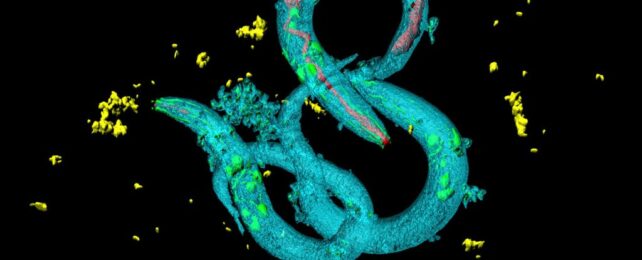

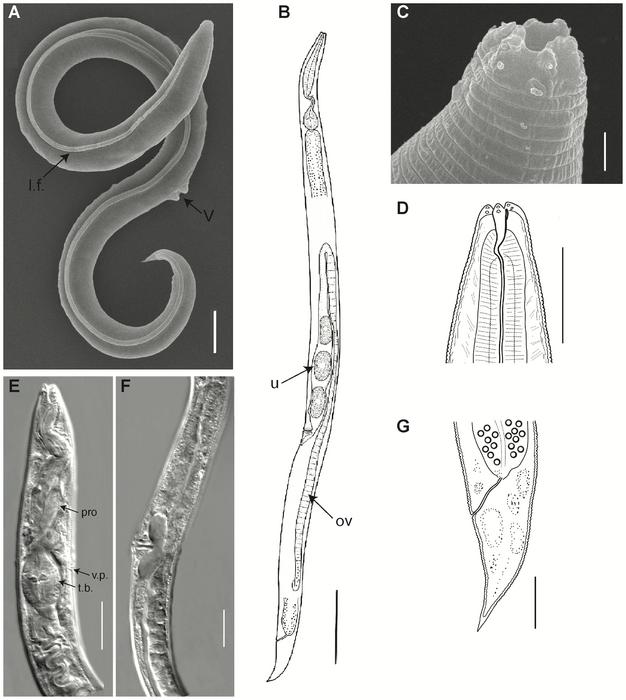

After reviving the frozen worm in the lab and cultivating it for over 100 generations, researchers, led by experts at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, ran a genome analysis.

They claim this creature is a newly recorded species, which they call Panagrolaimus kolymaensis.

To date, scientists know of very few animals capable of suspending themselves in a limbo-like state in response to tough environmental conditions.

Tardigrades, nematodes, and microscopic aquatic organisms, called rotifers, are just a few of the animals known to enter cryptobiosis. For all we know about the unique state of life, these animal could very well remain in this desiccated, or dried out, state 'indefinitely' – or at least until conditions are better for survival.

The longest recorded time spent in cryptobiosis among living worms is only 39 years.

Even tardigrades have only re-entered their normal metabolic state after 30 years of a frozen one.

The new crytobiosis queen is tens of thousands of years older than that.

The ancient worm was found in Siberian permafrost, roughly 40 meters deep. When researchers dated some plant material found near the creature, they settled on an initial freezing period somewhere between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago.

This beats another ancient roundworm, of the genus Plectus, which was also found frozen in Siberia and which was dated to around 42,000 years ago in 2018.

Both nematodes are nearly twice as old as an ancient rotifer from Siberia, which was recently revived after 24,000 years of cryptobiosis.

When researchers compared the genomes of P. kolymaensis to one of its living relatives, Caenorhabditis elegans, they found a lot of overlapping genes between the soil worms. Many of the shared genes are tied to mechanisms involved in surviving harsh environmental conditions.

This is interesting, as C. elegans is usually found in temperate regions, hiding in rotting fruit or plants.

The authors of the study say their findings "indicate that by adapting to survive cryptobiotic state for short time frames in environments like permafrost, some nematode species gained the potential for individual worms to remain in the state for geological timeframes".

The team now wants to figure out what role these shared genes play in cryptobiosis, and whether there is an upper limit to how long nematodes can remain in this mysterious state.

"These findings have implications for our understanding of evolutionary processes, as generation times may be stretched from days to millennia, and longterm survival of individuals of species can lead to the refoundation of otherwise extinct lineages," the authors of the paper write.

There's even a chance that unlocking the secrets of long-term cryptobiosis could provide scientists with a better way to store cells and tissues over long periods of time.

The study was published in PLOS Genetics.