New fossils found in China reveal marine reptiles from the Triassic Period were sifting tiny edibles from copious amounts of water long before modern whales made it cool.

Analysis of the skulls of two recently discovered specimens of Hupehsuchus nanchangensis by researchers from China and the UK identified structures that allowed the animals to scoop up large amounts of water for sifting out prey, in a process known as filter feeding.

Modern baleen whales eat this way but it seems Hupehsuchus, an extinct genus of 1 meter (3 foot) long marine reptiles closely related to ichthyosaurs, figured it out as early as 250 million years ago.

"We were amazed to discover these adaptations in such an early marine reptile," says paleontologist Zichen Fang from the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, lead author of the research.

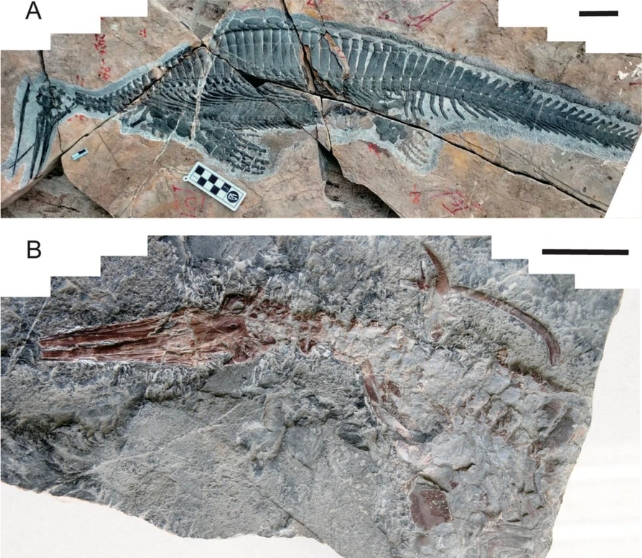

Both pieces of fossil evidence come from the Jialingjiang Formation in China. One is an almost complete skeleton, while another has been mostly preserved from head to clavicle area.

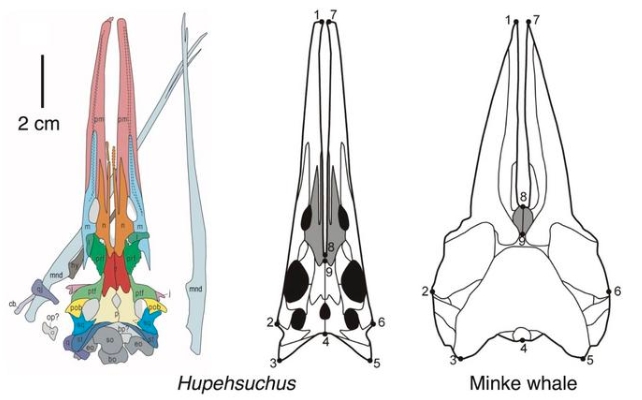

As part of the analysis, Fang and team compared the skull of the complete skeleton specimen to skulls from 130 amniote species; including baleen whales (mysticetes), toothed whales (odontocetes), seals (pinnipeds), crocodilians, birds, and the platypus.

The team says the skull structure of Hupehsuchus implies it evolved convergently with modern baleen whales, meaning the different species developed similar traits over time.

"We suggest it had independently evolved some form of baleen," says Li Tian, a biogeologist from the University of Geosciences Wuhan.

Hupehsuchus had a large mouth with long, slender, flexible lower jaws – great qualities for filter-feeding more efficiently.

"The long snout was composed of unfused, strap-like bones, with a long space between them running the length of the snout," says Long Cheng, a paleontologist from the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey.

"This construction is only seen otherwise in modern baleen whales where the loose structure of the snout and lower jaws allows them to support a huge throat region that balloons out enormously as they swim forward, engulfing small prey."

The team found the Hupehsuchus skulls also have grooves and notches along the edges of their jaws, suggesting Hupehsuchus used soft tissues like baleen to push water out of its rather spacious mouth.

"Modern baleen whales have no teeth, unlike the toothed whales such as dolphins and orcas," explains Tian.

"Baleen whales have grooves along the jaws to support curtains of baleen, long thin strips of keratin, the protein that makes hair, feathers and fingernails.

It's unclear where baleen came from in the whale's evolutionary past – the best evidence indicates their early ancestors went through a stage where they had both teeth and baleen before losing their teeth completely to become the filter-feeding baleen whales we know today.

Fang and colleagues add that Hupehsuchus' rigid trunk means it was a slow swimmer and probably used a continuous ram filter feeding method, like bowhead and right whales, snacking on crowded areas of plankton near the water surface.

Fierce competition for food might have prompted Hupehsuchus to adopt this diet so early in its evolutionary history.

Only around 4 percent of marine species survived the rising temperatures and acid rain of the profound mass extinction period around 252 million years ago, known as the 'Great Dying'. Hupehsuchus emerged not long after.

"The hupehsuchians lived in the Early Triassic, about 248 million years ago, in China and they were part of a huge and rapid re-population of the oceans," says paleontologist Michael Benton from the University of Bristol in the UK.

The authors note it took some 30 million years for whales to evolve filter-feeding adaptations, so Hupehsuchus' achievements are remarkable.

"This was a time of turmoil," Benton says. "It's been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time."

The study has been published in BMC Ecology and Evolution.