Humans have been intentionally changing their bodies for many thousands of years, but there's no denying that one of the most fascinating practices is that of skull modification.

Around the world, throughout history, many cultures have artificially and intentionally altered the shapes of their skulls.

Although the practice appears elsewhere in Asia, evidence of individuals deforming their skulls on purpose in Japan is scarce. There's just one place where it may have taken place: the island of Tanegashima, from around the 3rd to 7th centuries CE.

In contrast to other examples, however, the potential modifications are subtle. So subtle, other less intentional factors couldn't be ruled out.

Now, an in-depth analysis has confirmed it. The people who lived on what is now known as the Hirota site set out to alter the shapes of their skulls, both men and women alike.

"One location in Japan that has long been associated with cranial deformation is the Hirota site on the Japanese island of Tanegashima, in Kagoshima Prefecture. This is a large-scale burial site of the Hirota people who lived there during the end of the Yayoi Period, around the 3rd century CE, to the Kofun Period, between the 5th and 7th century CE," says anthropologist Noriko Seguchi of Kyushu University in Japan.

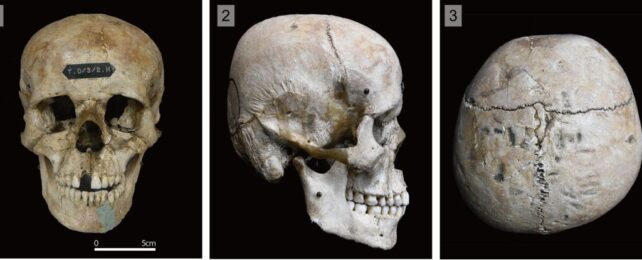

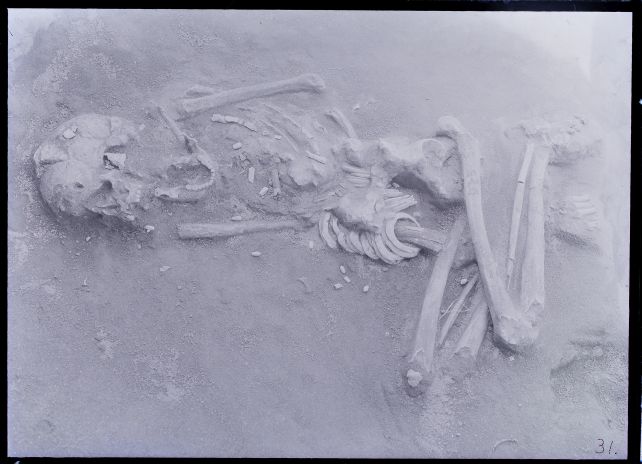

"This site was excavated from 1957 to 1959 and again from 2005 to 2006. From the initial excavation, we found remains with cranial deformations characterized by a short head and a flattened back of the skull, specifically the occipital bone and posterior parts of the parietal bones."

The Hirota site is an extensive burial ground. Between the two excavations, hundreds of full and partial skeletons, and thousands of grave goods, were retrieved, providing an extensive corpus for analyzing the Hirota culture. However, whether or not the skulls were intentionally modified, or whether the skull shape was the product of an unintentional process, was unclear.

Seguchi and her colleagues sought to solve the mystery, with a comprehensive comparative analysis of 2D images and 3D scans.

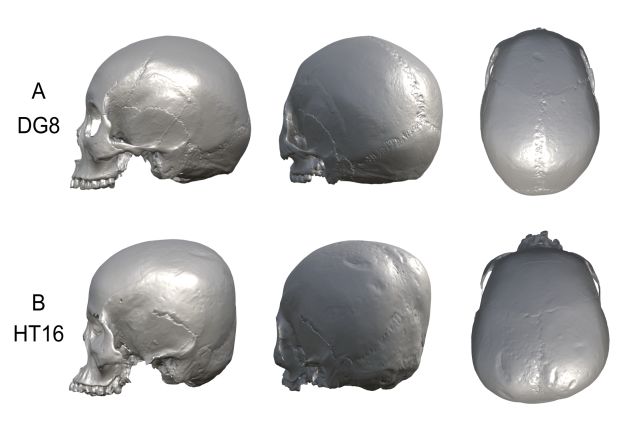

The researchers added skulls from Jomon people, who lived on Kyushu prior to the Yayoi Period; and a contemporaneous people from another island, the Yayoi Doigahama, to their study for comparison. In all, the study included 19 Hirota skulls, 9 Jomon skulls, and 28 Doigahama skulls.

The researchers made a visual comparison between the groups, followed by a statistical analysis of the shapes and contours of the skulls.

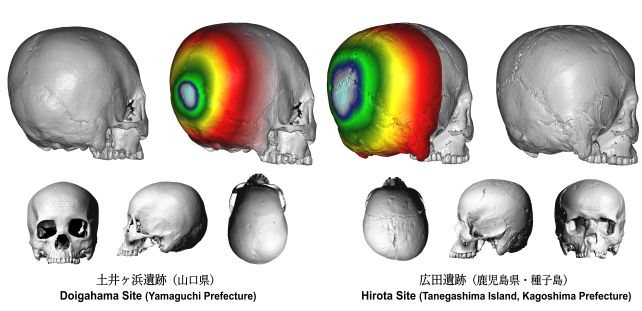

They found distinct characteristics in the Hirota skulls consistent with modification that were not found in the Jomon and Doigahama skulls. The backs of the skulls were distinctly flattened, and the crania had bulges, asymmetries, and depressions that indicated that the shape had not occurred naturally.

The most likely explanation, the team found, is a cultural exercise that was performed by the Hirota and not the other communities.

"Our results revealed distinct cranial morphology and significant statistical variability between the Hirota individuals with the Kyushu Island Jomon and Doigahama Yayoi samples," Seguchi explains.

"The presence of a flattened back of the skull characterized by changes in the occipital bone, along with depressions in parts of the skull that connects the bones together, specifically the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures, strongly suggested intentional cranial modification."

It's unclear why the Hirota people engaged in this skull-shaping practice, but it didn't seem to be based on sex. Men and women equally had squished skulls, suggesting it may have had something to do with reinforcing cultural identity – a way of standing out against other nearby people.

"Our findings significantly contribute to our understanding of the practice of intentional cranial modification in ancient societies," Seguchi says. "We hope that further investigations in the region will offer additional insights into the social and cultural significance of this practice in East Asia and the world."

The research has been published in PLOS ONE.