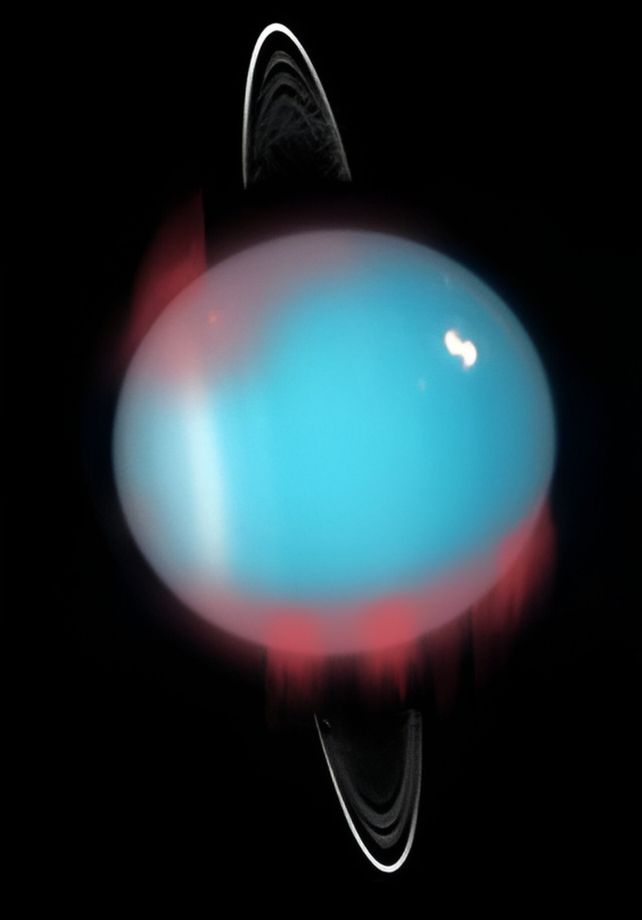

In data nearly 20 years old, scientists have finally confirmed the presence of infrared auroras, glowing in the northern regions of Uranus.

It's a discovery that allows astronomers to fill in some of the unknowns about the Uranian auroras, and perhaps shed some light on why the planet is so much hotter than it should be, so far from the Sun.

"The temperature of all the gas giant planets, including Uranus, are hundreds of degrees Kelvin/Celsius above what models predict if only warmed by the Sun, leaving us with the big question of how these planets are so much hotter than expected?" says astrophysicist Emma Thomas of the University of Leicester in the UK.

"One theory suggests the energetic aurora is the cause of this, which generates and pushes heat from the aurora down towards the magnetic equator."

Auroras are created when energetic particles are accelerated towards a planet, usually along magnetic field lines, and interact with particles, usually in its atmosphere, when they rain down upon it. The ionization that results from this interaction produces a glow.

They are very far from an exclusive Earth phenomenon, although they can look very different on different worlds.

Jupiter's powerful, permanent auroras blaze in ultraviolet light, as do those on Mars. Venus' are similarly green to Earth's. Mercury has no atmosphere; its auroras manifest as X-ray fluorescence from the minerals on the surface.

Since 1986, we've known about ultraviolet auroras on Uranus, and there may even be an X-ray component. Scientists have thought that it must have infrared auroras, too, like those seen at Jupiter and Saturn. However, although they've been looking since 1992, evidence of this glow has proven elusive.

Although Uranus probes have, sadly, been few and far between, Thomas and her team thought that we might have detected infrared auroral emissions without realizing.

In 2006, the NIRSPEC instrument (Near InfraRed SPECtrograph) at the Keck Observatory was used to collect 6 hours of observations of Uranus. It was here that the researchers decided to look.

They made a careful study of 224 images, looking for signs of a specific particle – ionized triatomic hydrogen (H3+). The strength of this particle's glow changes with temperature, which means it can be used to measure how hot or cold something is.

But when the researchers found signs of H3+ in their data, they found that it increased in density, without altering the temperature of the planet's atmosphere.

This is consistent with the increase in upper atmosphere ionization the astronomers expect to see with an infrared aurora. Therefore, they say the signature finally represents the discovery of infrared auroras in the atmosphere of Uranus.

Since auroras are connected to both the atmosphere and the magnetic field of Uranus, the discovery adds some information that may help us better understand some of the planet's weirder mysteries. For example, its magnetic field is sort of a hot mess – not only tipped sideways, but asymmetrical to boot.

And it could help us better understand the abundance of Neptune- and Uranus-like worlds out there in the wider galaxy, and assess their suitability for life, Thomas says. That's because we can study the way these alien worlds glow to draw inferences about their own atmospheres and magnetospheres, based on our observations of Uranus.

"This paper is the culmination of 30 years of auroral study at Uranus, which has finally revealed the infrared aurora and begun a new age of aurora investigations at the planet," she says.

"Our results will go on to broaden our knowledge of ice giant auroras and strengthen our understanding of planetary magnetic fields in our Solar System, at exoplanets and even our own planet."

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.