A new study reveals a previously undiscovered way that we can feel light touches: directly through our hair follicles.

Before now, it was thought that only nerve endings in the skin and around the hair follicles could transmit the sensation.

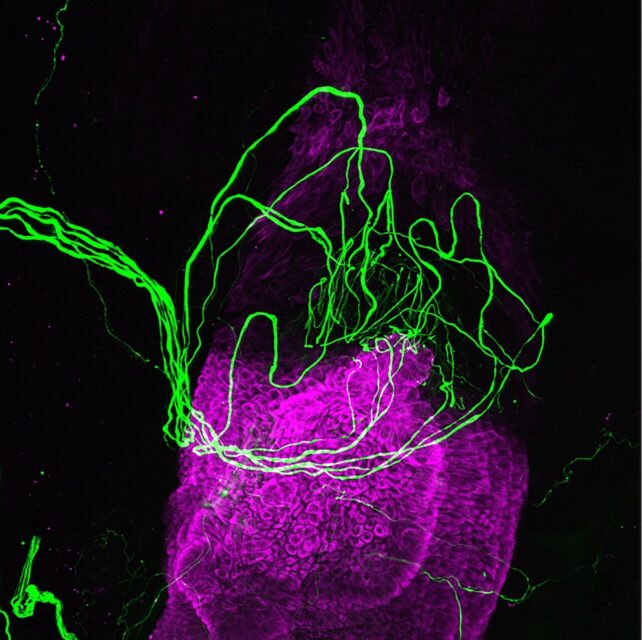

The team behind the study, led by researchers from Imperial College London in the UK, used an RNA sequencing process to find that cells in part of the hair follicle called the outer root sheath (ORS) had a higher percentage of touch-sensitive receptors than equivalent cells in the skin.

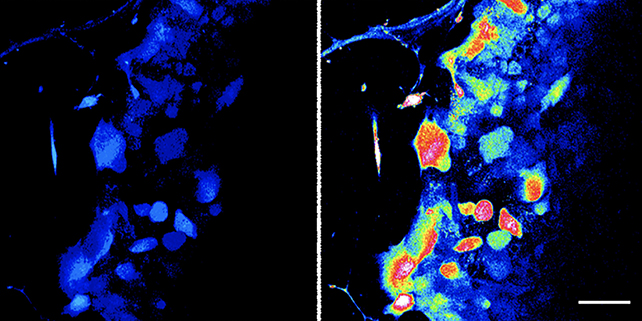

From there, the researchers produced lab cultures of human hair follicle cells together with sensory nerves.

When the hair follicle cells were mechanically stimulated, the sensory nerves next to them were also activated – showing that touch had been registered.

What's more, the experiments revealed that the neurotransmitters serotonin and histamine were being released by the ORS cells through tiny sacs called vesicles, as a way of signaling to the surrounding cells.

"It's an exciting finding as it opens up so many more questions for these cells: why do they have this role, and what else can we learn from them about how our skin senses touch?" says neural engineer Parastoo Hashemi from Imperial College London.

Touch-sensing nerve cells are known as mechanoreceptors. They're the reason we can feel everything from a light breeze to a firm press. In this case, the hair follicle cells were interacting specifically with low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs), capable of feeling gentle touches.

While it was already known that body hair plays an important role in the sense of touch, the researchers have revealed a more detailed biological interaction between ORS cells and LTMRs beyond a simple mechanical response. One big remaining question is 'why?'.

"This is a surprising finding as we don't yet know why hair follicle cells have this role in processing light touch," says bioengineer Claire Higgins from Imperial College London.

"Since the follicle contains many sensory nerve endings, we now want to determine if the hair follicle is activating specific types of sensory nerves for an unknown but unique mechanism."

What's also worth noting from this research is that the experiments were repeated using skin cells rather than hair follicle cells: in this case, histamine was released, but very little serotonin. That suggests something unique about what the ORS cells do.

Considering that histamine plays a significant role in several inflammatory skin diseases, including eczema, it's possible that further research into the way that hair follicles detect touch could also lead to improved treatments and preventative measures.

"Our work uncovers a new role for skin cells in the release of histamine, with potential applications for eczema research," says Higgins.

The research has been published in Science Advances.