If you're keen to live a more meaningful existence, consider framing your life as a hero's journey, says a team of scientists who conducted eight studies that "point to a profound connection between the lives we live and the stories we tell."

The hero's journey structure has been used by storytellers for hundreds of years to describe the narrative of an ordinary character on a wild adventure, where they overcome obstacles before returning home a changed person, or lion, fish, etc.

But it's not only Simba from The Lion King or Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz who can live out stories like this. Involving a total of 2678 participant responses across their studies, the researchers from the US and Canada used their initial findings to develop a "restorying" intervention that appears to help people enrich their sense of meaning.

"It might seem difficult for people to imagine themselves as mythical heroes, but our results suggest this is not required," behavioral scientist Benjamin Rogers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his colleagues write in a published paper on the studies.

"The lives of everyday people can – and do – have the elements of a Hero's Journey and most any life can be restoried as such".

Mythologist Joseph Campbell first outlined the hero's journey in 1949, drawing attention to a common narrative structure behind some of the most enduring stories throughout history. The team wanted to see if it could be a blueprint for crafting an interesting account of one's own life, and if this might impact how meaningfully we perceive our personal journeys.

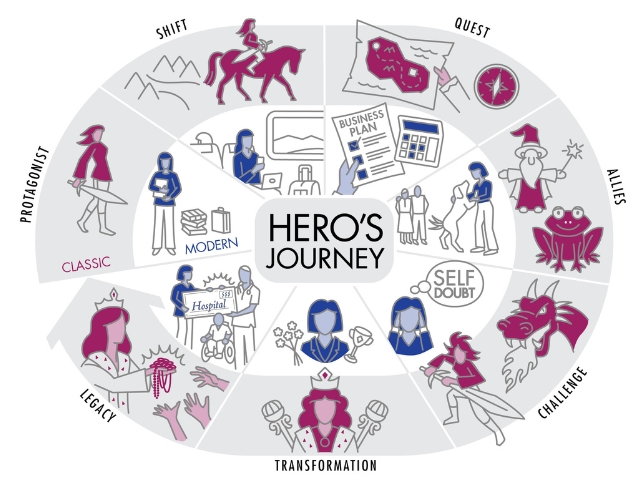

They condensed Campbell's somewhat dated classic 17 steps into seven elements that translate to modern life: a lead protagonist, a shift of circumstances, a quest, a challenge, allies, a personal transformation, and a resulting legacy.

Next, they created and tested a 21-item Hero's Journey Scale (HJS) to measure how closely the hero's journey matched people's life stories, focusing on the continuity of individuals' life narratives.

For example, to gauge someone's openness to change for the shift element, the HJS would ask them to rate how often they encounter novelty instead of asking bluntly whether they had ever experienced a significant shift in their circumstances.

The authors gathered over 1,200 individual narratives from a variety of sources, including online and in-person interviews.

Their analysis found that those whose life stories contained more of their seven hero's journey elements also reported higher levels of meaning, higher levels of flourishing (feeling like they were a good person living a good life), and lower levels of depression.

"People who use the hero's journey to tell their story appear better equipped to frame the ambiguity of life as meaningful to them," the researchers write.

These 'heroic' individuals reported more novel experiences, ambitious goals, supportive friends, and so on, than the other participants.

Based on these results, the authors devised a restorying intervention with prompts to encourage further sets of participants to see their lives through the lens of a hero's quest. Prompts were organized so the seven elements built on one another as people told their life stories.

These participants were asked questions like, "What change of setting or novel experience prompted your journey to become who you are today?" and given sentence starters like, "My journey to who I am today began as a result of…" to help them reflect on how their lives exhibited evidence of shift.

Rogers and his team discovered the intervention aided participants in conceptualizing their lives as a hero's journey, which in turn increased how meaningful they reported finding their lives.

"Restorying intervention participants appeared to be more resilient to life's challenges," writes the team, "both in terms of how they viewed their problems and the tactics they employed to address them."

The hero's journey restorying intervention has the potential to increase both positive and negative behaviors, the authors note. It might lead to more optimistic outlooks, healthy coping mechanisms, and altruistic actions. Also, it could make people more likely to act narcissistically or devote themselves to misguided causes.

They suggest further studies should explore how seeing oneself as a hero on a journey might affect behavior in more detail. And all studies were conducted in the US, where the narrative is popular, so the outcome could vary elsewhere.

"Examining how the dynamics of different stories correspond to personal narratives is a rich area for future research," the authors write.

"We hope that our restorying intervention provides a template for future researchers to use in exploring the role of different narratives in people's lives."

The research has been published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.