A burst of light from a newborn black hole billions of light-years away in space and time has struck Earth with such power, it rattled the planet's upper atmosphere.

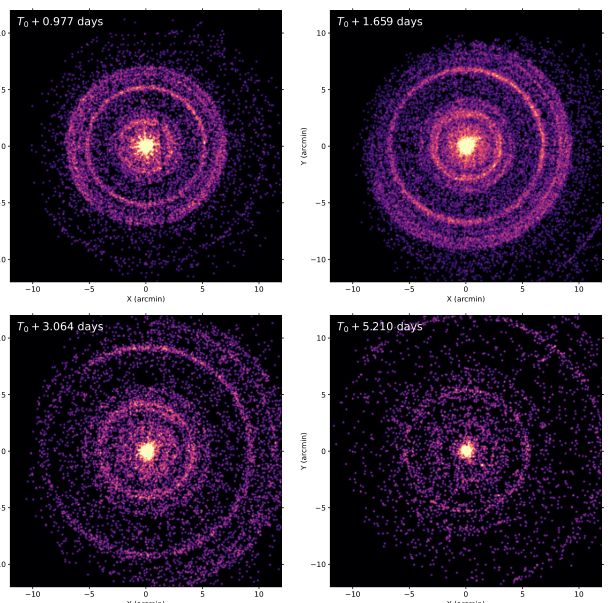

The gamma-ray burst GRB 221009A shattered records as it flared in the darkness of space in October 2022 some 2.4 billion light-years from Earth, its light blazing with up to 18 teraelectronvolts of energy in what is regarded as the brightest space explosion ever recorded.

Now, scientists have determined that the explosion was so powerful that it caused large variations in the electric field of Earth's ionosphere, at an altitude of some 500 kilometers (310 miles).

"In this work we present the evidence of variation of the ionospheric electric field at about 500 kilometers induced by the strong gamma-ray burst [that] occurred on October 9th, 2022," write a team led by astrophysicist Mirko Piersanti of the University of L'Aquila and the National Institute of Astrophysics in Italy.

"Using both satellite observations and a new ad hoc developed analytical model, we prove that the GRB 221009A deeply impacted on the Earth's ionospheric conductivity, causing a strong perturbation not only in the bottom-side ionosphere, but also in the top-side ionosphere (at around 500 kilometers)."

Gamma radiation is the most energetic part of the electromagnetic spectrum, followed by X-radiation. Gamma-ray photons have a billion to a trillion times the energy of photons in the visible part of the spectrum, and are emitted by highly energetic events such as supernovae and hypernovae, as well as smaller energetic events, such as solar flares.

This radiation is not really anything to worry about, on a day-to-day basis; it's absorbed by Earth's atmosphere before it can get anywhere close to the surface. That's why we need space telescopes to detect it. What it can do, however, is interact with the atmosphere at high altitudes.

On rare occasions, scientists have recorded gamma-ray and X-rays from unusually powerful gamma-ray bursts interact with Earth's lower ionosphere.

The ionosphere is a relatively thick layer of Earth's atmosphere, between roughly 50 and 1000 kilometers (about 30 to 600 miles) in altitude, overlapping several other atmospheric layers. It's so named because it's the part of the atmosphere where extreme ultraviolet and X-radiation from the Sun ionize the atmospheric atoms and molecules, creating a bunch of loose electrons.

The ionosphere reflects the radio waves we use for communication and navigation. When a powerful event occurs, such as a solar flare, we can record the changes it makes in the lower ionosphere by recording the changes in the way very low-frequency radio waves reflect off it.

This was how, almost immediately, scientists were able to observe changes in the lower ionosphere, at altitudes between 60 and 100 kilometers, coinciding with the detection of GRB 221009A back in October 2022. It was so powerful, they said, that its effects were comparable to those of a solar flare.

The Sun is 150 million kilometers away. GRB 221009A's light traveled 22.7 sextillion kilometers. That should tell you something about how powerful that explosion was.

But the effect of gamma-ray bursts hasn't been studied on the entire ionosphere, so Piersanti and his colleagues sought to detect its effect on the layer's topside. For this, they tapped into satellite data, and, for the first time, were able to detect and measure electromagnetic field variations at high ionospheric altitudes.

In fact, the effects were huge. The gamma-ray burst itself only lasted for about 7 minutes. The recorded effect on the ionosphere persisted for about 10 hours. Knowing this, the researchers say, can help us better understand and model the effects of distant explosions on Earth's atmosphere – and predict what might happen were one to occur close by.

"The unprecedented photon-flux associated to the GRB221009A deeply impacted on the Earth's ionospheric conductivity, causing a strong perturbation not only in the bottom side ionosphere, where it is typically observed using ground VLF antennas, but also in the top-side ionosphere (at around 500 kilometers)," the researchers write.

"In fact, a huge variation of the ionospheric electric field, induced by the strong ionospheric conductivity change, was detected in the top side ionosphere (507 kilometers) as a consequence of a gamma-ray burst impact."

And none of us even noticed a thing. Isn't our little protective atmospheric bubble wonderful?

The research has been published in Nature Communications.