At the start of the 20th century, psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer became the first person to notice the strange clumps and tangles in the brain of a person who had died with dementia.

These bundles of amyloid beta proteins have since become the dominant hypothesis for what causes Alzheimer's disease. And, despite decades of failed studies, finding ways to clear them away has remained an obsession.

Now, in two trials, a drug designed to eradicate these sticky plaques has failed to preserve the cognitive abilities of people with early Alzheimer's disease compared to people given a placebo.

The monoclonal antibody gantenerumab did significantly reduce the amount of amyloid beta in the brain as intended, but this did not translate into improvements in cognitive function.

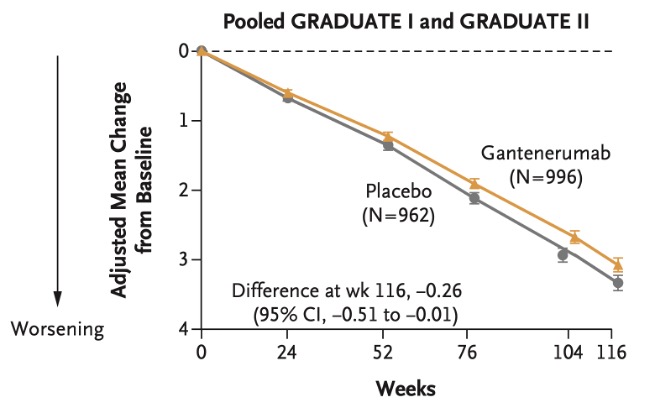

"Among persons with early Alzheimer's disease, the use of gantenerumab led to a lower amyloid plaque burden than placebo at 116 weeks but was not associated with slower clinical decline," the researchers reported in their paper covering the two drug trials.

These results arrive as the amyloid hypothesis reaches a critical juncture in its history – with pharmaceutical companies controversially winning anti-amyloid drug approvals based on thin evidence.

It also follows on the heels of an explosive investigation by Science that threw doubt on one of the early amyloid studies.

In each gantenerumab trial, almost 1,000 older people from 30 countries were randomly assigned to receive gantenerumab injections or a placebo every few weeks for around two years.

Their cognitive abilities were measured on a score from 0 to 18 using the Clinical Dementia Rating scale–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

"Depending on one's perspective, the results of the antibody trials to date either reinforce confidence in this therapeutic approach and its clinical meaningfulness or support a view that the effects are small, unreliable, and barely distinguishable from no effect," Lon Schneider, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Southern California, writes in a linked editorial.

It is surprising that gantenerumab showed no benefits when two other drugs with similar mechanisms have been fast-tracked by the FDA, writes Schneider, who also notes the possibility that the two-year trial of gantenerumab was too short to show a benefit to patients, or that by splitting the trial into two separate studies (GRADUATE I and II) the impact was watered down.

Aducanumab and lecanemab were given accelerated approval by the FDA on the basis that they clear amyloid beta from the brain.

Like gantenerumab, these two drugs contain synthetic antibodies that bind to the amyloid beta protein in the brain, which is thought to flag them for removal by the immune system.

But there's still controversy around whether aducanumab and lecanemab have meaningful benefits for patients.

The impact of aducanumab on slowing cognitive decline in clinical trials was mixed, with one trial showing an effect and another failing to show a clinical benefit.

In a clinical trial, people with Alzheimer's taking lecanemab experienced a 27 percent decrease in cognitive decline than the placebo group over 18 months. But, on a scale from 0 to 18, the difference between the two groups was just 0.45 points, which might be too small to make a meaningful difference in the lives of patients.

There have also been concerns raised about three deaths from brain bleeds and seizures in the lecanemab study. At an estimated cost of US$26,500 per year, it's unclear to some experts whether this drug is worth the risk.

We've spent more than a century pondering the role of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Whether this will pay off for patients and families desperate for treatments remains to be seen.

The results of the two trials were reported in The New England Journal of Medicine.