Fragments of ancient rock and bone in Eastern Asia are changing our understanding of the history of human migration.

They're artifacts found in the Shiyu site of northeastern China, and new analysis has revealed that they were created by Homo sapiens some 45,000 years ago.

It's the earliest evidence of modern humans in Eastern Asia, suggesting that Homo sapiens were established at Shiyu by then, and provoking a new interpretation of the cultural artifacts previously found at the site.

"The site reflects a process of cultural creolization – the contact between societies and relocated peoples – blending inherited traits with novel innovations, thus complicating the traditional understanding of Homo sapiens' global expansion," explains archaeologist Francesco D'Errico of the University of Bordeaux.

Shiyu has been known for decades as a place of archaeological significance. It was inhabited for a long time – the sedimentary sequence is 30 meters (98 feet) deep, and the layers therein were deposited over tens of thousands of years. Buried in the sediment, archaeologists have found a rich assortment of tools and artifacts made and used by the people who lived there.

Establishing who those people were, and how long they lived there, has been an ongoing project. The first excavations, in 1963, yielded thousands of objects: 15,000 stone artifacts, thousands of pieces of bone and teeth… and one single hominid fossil, a piece of skull bone identified as belonging to Homo sapiens.

However, most of the collection was subsequently lost, including the skull fragment.

Undeterred, scientists undertook another excavation in 2013. Led by paleoanthropologist Shi-Xia Yang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, an international multidisciplinary team has now worked to characterize the site in detail.

They selected a large number of the available artifacts, and analyzed them closely. They studied animal bones found at the site. And they performed new dating analysis, using radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence techniques to accurately date samples taken from different sections of the sediment sequence.

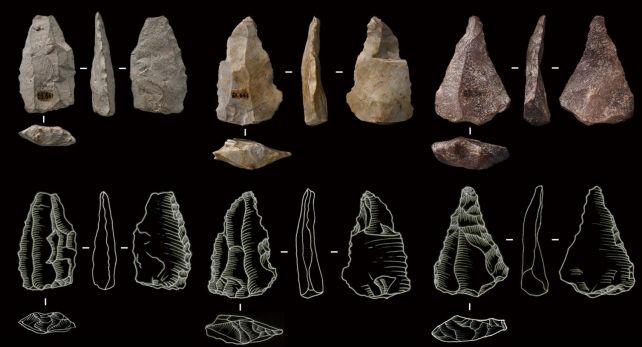

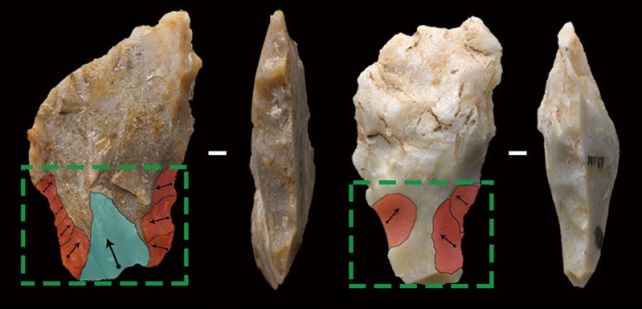

The dating revealed that the very oldest layer of the sequence was deposited around 45,000 years ago. And the analysis of the artifacts revealed a range of technological skills, such as the Levallois technique for knapping stone, developed in Europe around 250,000 years ago.

The assemblage also includes tanged and hafted projectile points with evidence of impact fractures, suggesting hunting skill. And there was obsidian that could only have been sourced from a large distance, at least 800 to 1,000 kilometers (500 to 620 miles), away, suggesting trade or travel or both.

Other interesting items include a worked bone tool, and a disk of graphite with a hole in its center, the purpose of which remains unclear (although the latter, the researchers speculate, could have been a large button of some kind).

The animal bones at the site were also fascinating. Most of them were equid, or horse bones, mostly adults. Many of them showed cut marks indicative of butchering, suggesting that the inhabitants of the Shiyu site were skilled hunters who preyed on horses.

It paints a complex and inspiring picture. "The amalgamation of diverse cultural traits signifies a complex and innovative adaptation by our ancestors during their expansion," Yang says.

Combined with the still-lost fragment of skull, the discovery represents an important piece of human history, the researchers say. Perhaps future work could uncover more clues about the mysterious people who once inhabited Shiyu, leaving behind traces of their cunning and resourcefulness, to be uncovered by their descendents, tens of thousands of years later.

"Understanding the complexities of our ancient past can offer invaluable insights into the diverse pathways taken by our ancestors and the richness of human adaptation," says archaeologist Michael Petraglia of Griffith University in Australia.

"This discovery at Shiyu unveils a captivating story of early human migration and cultural fusion, expanding our knowledge of our ancient origins and the remarkable adaptability of Homo sapiens."

The research has been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.