According to an analysis of hundreds of preserved bird specimens from museum collections around the globe, there's a specific set of feather rules behind the power of flight.

These newly discovered rules allow scientists to better predict which dinosaurs could fly too.

"Theropod dinosaurs, including birds, are one of the most successful vertebrate lineages on our planet," says Field Museum of Natural History paleontologist Jingmai O'Connor. "One of the reasons that they're so successful is their flight. One of the other reasons is probably their feathers, because there's such versatile structures."

Their new data could settle some old paleontological debates over whether flight evolved in dinosaurs on more than one occasion.

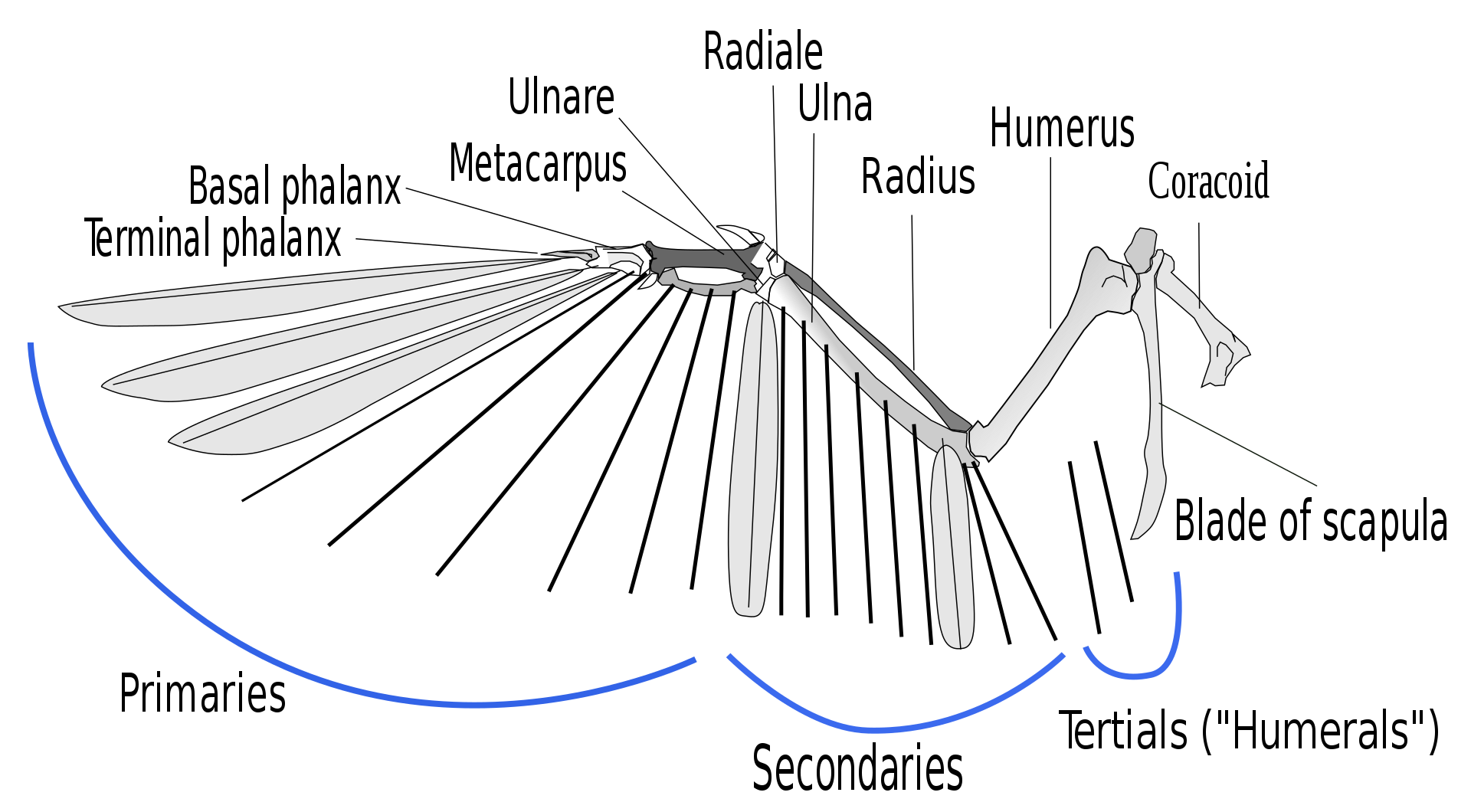

Examining wing feathers of 346 different species of birds from museums around the world, Field Museum of Natural History ornithologist Yosef Kiat discovered an interesting trend. From the tiniest hummingbird to the fiercest eagle, all flying birds had 9 to 11 asymmetrical flight feathers called primaries.

But the number of primary feathers in flightless birds varied immensely. Emus lack them completely, while penguins fancy themselves up with 40.

"It's really surprising, that with so many styles of flight we can find in modern birds, they all share this trait of having between nine and eleven primary feathers," says Kiat. "And I was surprised that no one seems to have found this before."

The number of primaries, along with feather symmetry and wing proportions accurately reflect the flight capacity of all known modern birds.

Looking at fossils up to 160-million-years-old the researchers identified which bird ancestors shared these traits, and were therefore likely to have been able to fly. Out of 35 different species of extinct birds, Kiat and O'Conner identified some that had the right feathers for flight, and others that did not.

The likely flyers include Archeopteryx, considered to be one of the earliest bird-like animals. While there's debate over the true relationship between Archeopteryx and birds, tiny four-winged dinosaurs called Microraptors also had these features, despite not being directly related to birds at all.

"It was only recently that scientists realized that birds are not the only flying dinosaurs," explains O'Connor.

Oddly, Caudipteryx possessed the correct number of primary feathers but they were almost completely symmetrical, "almost certainly" ruling out flight. The researchers speculate that Caudipteryx's ancestor was likely able to fly but the genus had since lost this ability.

"Our results here seem to suggest that flight only evolved once in dinosaurs," states O'Connor.

Their analysis indicates the anatomy required for flight evolved in a species ancestral to all these pennaraptoran groups before they diversified. Some, like Caudipteryx, became flightless early on. Those like Microraptors retained their flight but ended up part of an evolutionary dead end. Others went on to become modern birds.

Kiat and O'Connor point out claims suggesting flight evolved multiple times in dinosaurs were based on skeletal data alone.

"We argue it is impossible to assess flight potential in non-avian pennaraptorans without examining the structure of the feathers forming the wing itself," they write in their paper.

They believe we're still missing the earliest stages of wing evolution from our fossil records, so this is unlikely to be the final word in the debate.

This research was published in PNAS.