Climate change is having detrimental effects on children's health as an increasing number of infants are born preterm, presenting to hospital, and experiencing respiratory disease, putting society's most vulnerable at greater risk of death.

New research by an Australian team of scientists reviewing 163 health studies from across the world reveals an extremely troubling picture of how childhood health measures have already worsened as a result of climate change, which shows no sign of abating anytime soon.

An estimated 600 million people currently live in areas that expose them to temperatures outside of what's considered ideal for humans, and scientists predict that number will rise to 3 billion people by the end of the century.

That's bad news, given that the new research found temperature extremes associated with climate change have raised the risk of preterm birth to 60 percent on average.

The study also reports that an increase in airborne particles and allergens from climate events like wildfires, droughts, and irregular seasons is having a substantial impact on respiratory disease and perinatal outcomes.

Corey Bradshaw, a global ecologist from Flinders University in Australia, is concerned climate change could cause lifelong complications for millions of children around the world.

"We've crunched the data to show how certain types of future weather events will worsen particular medical issues in the population," he says.

"We identified many direct links between climate change and child health, the strongest of which was a 60 percent increased risk on average of preterm birth from exposure to temperature extremes."

Perinatal outcomes were shown to be impacted by temperature changes in 39 of the papers that Bradshaw and colleagues reviewed. Preterm birth was reported in 29 of these studies, making it the most common outcome associated with either exposure to temperature extremes or increases in ambient temperatures. But other studies also reported effects such as low birth weight, gestational age changes, premature membrane rupture and even pregnancy loss.

While temperature extremes had the greatest impact on child health, 16 of the 20 studies investigating the impact of air pollutants found they had at least some effect on child health outcomes.

Air pollution had a significant impact on respiratory diseases. For instance, at least seven different studies reported that increased concentrations of airborne particles coincided with a rise in the number of children presenting to hospital emergency departments with respiratory issues. Four of these studies specifically investigated pollution from wildfire smoke, which we are now inhaling more often than ever.

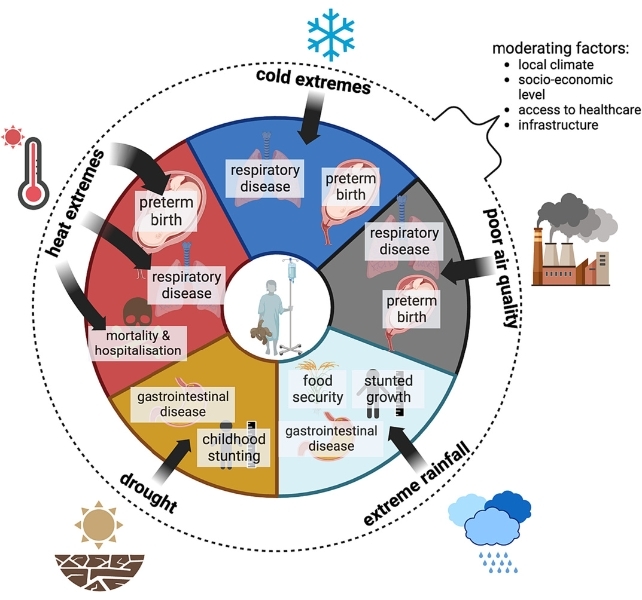

"The children's health issues we identified depend on weather extremes – cold extremes give rise to respiratory diseases, while drought and extreme rainfall can result in stunted growth for a population," the authors write.

"Given that climate influences childhood disease, social and financial costs will continue to rise as climate change progresses, placing increasing pressure on families and health services."

As the researchers point out, low- and middle-income countries are underrepresented in the research. So this bleak picture might actually be an under-estimation of how bad things are really getting, because most of the studies analyzed were conducted in high-income countries where children are better protected from the worst impacts of climate change.

According to the researchers, the key factors protecting children from the threat climate change poses to their health are economic stability and strength, access to quality healthcare, adequate infrastructure, and food security.

"Climate change is universal and adversely affecting all countries and people, and we must prepare societies for mounting threats to child health," says medical scientist Lewis Weeda from the University of Western Australia.

"The development of public health policies to counter these climate-related diseases, alongside efforts to reduce anthropogenic climate change, must be addressed if we are to protect current and future children."

This research has been published in Science of the Total Environment.