While you're peacefully dreaming, your brain is taking care of a few important maintenance tasks. A new study reveals more about the process that ejects waste material from the brain while we're snoozing.

The brain produces these waste substances as it expends energy and sucks up nutrients during the day. Taking out the trash is the job of the glymphatic system, however we don't yet have a full picture of how this network of drainage channels functions.

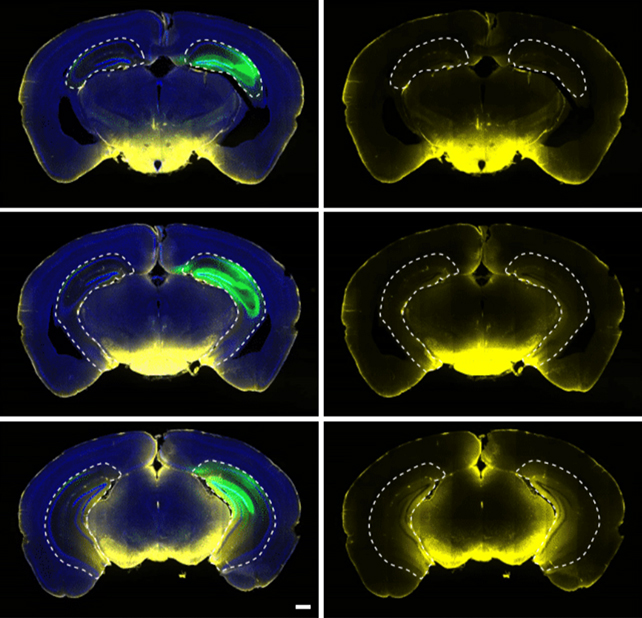

Researchers from Washington University in St Louis observed neurons coordinating electrical signals in mice. These signals generated rhythmic waves, which then helped to wash fluid through the brain, cleaning it up along the way.

"We knew that sleep is a time when the brain initiates a cleaning process to flush out waste and toxins it accumulates during wakefulness," says neuroscientist Jonathan Kipnis, from Washington University in St Louis. "But we didn't know how that happens."

Disabling specific regions in the mice brains prevented the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, showing that the brain wave patterns produced by the neurons were an essential part of the brain-cleaning process.

We already know that there are oscillating brain waves passing through our heads while we sleep, linked to everything from cognitive processes to consolidating memories. This new study suggests these patterns play a big role in tidying up the brain, too.

If scientists can get to a stage where we're able to manage this activity, it might open up new treatments for diseases that attack the brain. These diseases are often linked to the build-up of toxic materials that aren't properly washed away.

"These neurons are miniature pumps," says neuroscientist Li-Feng Jiang-Xie, from Washington University in St Louis. "Synchronized neural activity powers fluid flow and removal of debris from the brain."

"If we can build on this process, there is the possibility of delaying or even preventing neurological diseases, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease."

The team found that taller brain waves, with more amplitude, were more forceful at moving fluid around. It's possible that the brain cleans itself a bit like we might wash dishes: using broad strokes and then extra force to get rid of waste that's more difficult to shift.

Future research could look more closely at these variations, and at ways in which they might be controlled. As well as fighting brain disease, it might one day mean we can become more efficient sleepers too.

"One of the reasons that we sleep is to cleanse the brain," says Kipnis. "And if we can enhance this cleansing process, perhaps it's possible to sleep less and remain healthy."

"Not everyone has the benefit of eight hours of sleep each night, and loss of sleep has an impact on health."

The research has been published in Nature.